I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

Ah. This had to happen. Apparently, I’ve written sixteen of these newsletters, and this is the first week I discuss a novel I didn’t like that much.

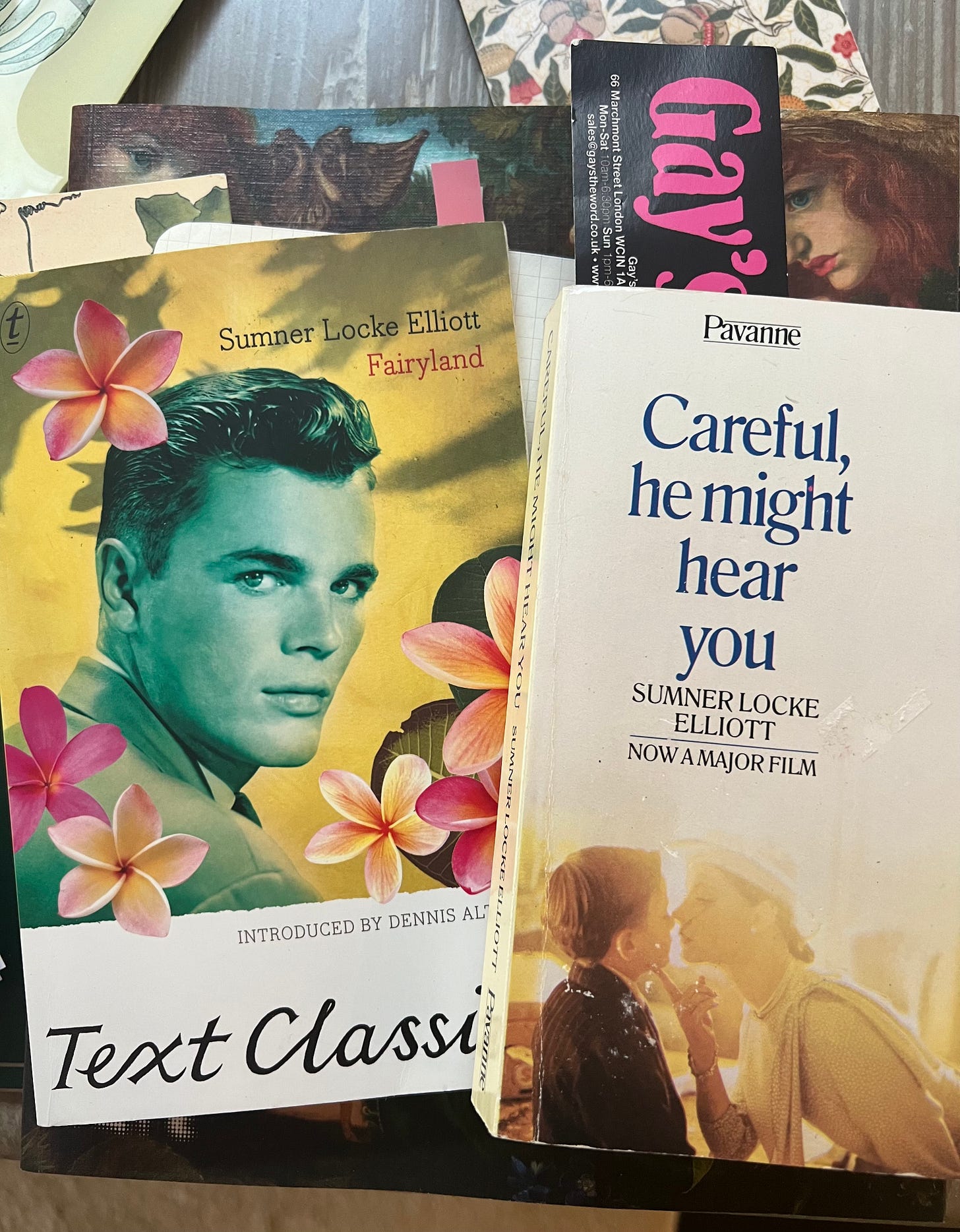

It’s Sumner Locke Elliott’s Fairyland, which in principle should be up my alley, not least because it’s about a writer, and a gay one to boot (any writer who says they don’t like books about writers is lying). But as I was reading it, I kept thinking about other writers; about Christopher Isherwood, Truman Capote, Edmund White – all of whom do this kind of thing much more successfully.

Anyway, I hope there’s something of interest below. And I heartily recommend Elliott’s Careful, He Might Hear You.

I’m on Threads, by the way – @samueladamsonwriter – but it’s got to be said, I’m hanging on by a thread. A week on, and Zuckerberg’s algorithm still doesn’t know me at all. Which is pleasing.

Have a lovely Sunday.

Sam

If Sumner Locke Elliott is known at all now, it’s probably for Careful, He Might Hear You (1963), his first, Sydney-set novel, about two sisters in a custody battle over their orphaned nephew, a boy known only as PS (his mother: ‘for that’s what he’ll be – a postscript to my ridiculous life’).1 It was made into a lovely film in 1983 starring Robyn Nevin and Wendy Hughes as aunts Lila and Vanessa, and it’s a lovely book for anyone interested, as I am, in the literary child’s-eye view – in what Maisie knows and does not know:

He listened to the conversation rumbling on above him, all about him and Vanessa and Logan [his father] and ‘custardy’; about who was going to have the ‘custardy’ of him. But what had desserts to do with Vanessa? He felt cold and funny inside and wished [they] would stop.2

Elliott drew on his life to create his fiction: his mother died soon after his birth, and he was raised by his aunts. As in his first novel, there is an orphan in his last, the Sydney-set Fairyland, though this one has a full name – Seaton Daly. Seaton is gay, becomes a writer, and emigrates to New York. Elliott was a gay Australian writer who made the same journey.

Fairyland was published in 1990, a year before Elliott died at the age of 73. Until then, gayness in his novels was coded; he was in his professional life closeted, though not, as the old joke goes, so deeply closeted that he was in Narnia. As Dennis Altman writes in his excellent Introduction to Fairyland’s Text Classics edition,

Beware Wikipedia’s claim that Elliott was uncomfortable with his sexuality and ‘never had any stable relationships’ – during the last decade of his life he was partnered with Whitfield Cook, who wrote the screenplay of Strangers on a Train, adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s novel.3

Altman wrote this in 2013, and I assumed when I read it this week that ten years on, the Wikipedia quote would no longer be there. The fact that it is probably indicates the extent of the indifference towards Elliott – and in particular towards his literary ‘coming out’.4

This is surely unfair – and yet I didn’t like Fairyland that much, and I also wonder what Altman really thinks of it: his Introduction is polite, not effusive.

The book is set in the 1930s and 40s, and follows Seaton from childhood to adulthood, from Sydney to New York, from bullied orphan to successful writer – although a key sequence concerns literary failure: Seaton writes a flop Broadway play, and Elliott, a playwright as well as novelist, captures the singular gruesomeness of those theatrical rats who, as the bad reviews dribble in, abandon the ship they’d sworn they loved. It is an intriguing and consoling account of homosexuality in 1930s-40s Australia: Seaton finds his lovers and sympathetic friends with relative ease, and there are vivid portraits of Sydney’s thriving gay subcultures. But there are, I think, two fatal weaknesses.

The first is that most of the women are caricatures – very disappointing from the writer of Careful, He Might Hear You, in which each of PS’s four aunts is beautifully drawn. The cousin who raises Seaton is impossibly daft and doting; and the blowsy nightclub performers, the Tallulah Bankhead-type lesbian actresses, and the shrews (no other word) who enter his life are too grotesque, too camp, too shrewish (arguably, most of the gay men are similarly caricatured). Only Seaton’s understanding friend Betty Jollivet – magnificent name, but you see: just a bit overdone – really convinces.

The second weakness is that Seaton is a character to whom things happen, and although there’s a long tradition of this type of detached protagonist in gay novels – Christopher Isherwood’s ‘I am a camera’ – I found his passivity and elusiveness alienating. It’s a long novel, and in episode after episode, from school to work to army to escape to New York, we get little sense of what Seaton feels about anything. In the penultimate chapter, he turns on a monstrous lover, the bisexual Skinner, and defends the young woman Skinner has dumped:

You have to spoil it, don’t you, there’s something in you compels you to spoil everything you touch and damage what’s precious to other people. All my life I’ve hung on to one important compensation for what I am. I’ve just loved and not expected love back because I wanted just to love and that’s saved me and made up for what people call the sin of it. You pervert it, Skinner, you pervert it.

This outburst is unusual, and powerful, yet it captures why I never felt engaged. Seaton has, indeed, not expected love. In the book’s most successful sequence, which makes it worth reading, he falls in love with a straight man, Athol, who in turn falls in love with Betty. Seaton’s gay friend Rat advises him:

Be a good sport about it, darling, it’s all you can be and you might as well start getting used to it, you’re going to have to be a good sport about it for the rest of your life.

Seaton’s denial of the expectation of returned love is the act of a good sport; and perhaps this is designed as an indictment – an indictment of the necessity for a gay man to be so noble, of mid twentieth-century provincial Australia and its homophobia. But – straight Betty and Athol aside – almost everyone Seaton meets is slightly sneered at (he and the narrator are more snobs than good sports), so it seems to me that Seaton’s denial could also be Elliott’s own internalised homophobia. Whatever it is, it’s entirely undramatic, and creates an emotional barrenness at odds with what is essentially a young man’s rite of passage.

In his Introduction, Altman links Fairyland with Patrick White’s The Twyborn Affair, the implication being, I think, that these explicitly gay statements by two of Australia’s towering twentieth-century gay authors – in whose other works gayness is often coded – are ‘lost’ novels. There’s a lot of beautiful stuff in Fairyland – one thing I loved was Elliott’s elegant use of prolepsis. On a weekend away with Betty and Athol, they go off together, and Seaton unexpectedly finds himself having quick, secretive sex with a colleague called Arnold. It’s a key moment in Seaton’s understanding of what it means to be homosexual in a heterosexual world, and the narrator tells us,

And thirty years later it would be Arnold he thought about in moments of tender loneliness, not Athol.

This is moving and truthful. The book is an important gay novel, a fascinating depiction of gay 1930s/40s Sydney by a gay man who was there. But if, in the event of disaster, there’s time to save only one Lost Queer Classic by a Dead White Australian Male, grab The Twyborn Affair.

Sumner Locke Elliott, Careful, He Might Hear You (New York: Harper & Row, 1963; repr. London: Pavanne, 1984), p. 13.

Elliott, p. 20.

Dennis Altman, Introduction to Elliott, Fairyland (New York: Harper & Row, 1990; repr. Melbourne: Text Classics, 2013), p. ix. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 181, 191, 300.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumner_Locke_Elliott> [accessed 15 July 2023].

I love the honesty of your review, Sam. It's disappointing when you really want to find something in a novel and it's lacking, although it sounds as though it was still a novel worth reading.

Very interesting. And I, for one, like that you are writing (very shrewdly) about something that underwhelms you. It complements and strengthens your other paeans of praise.

But at that this point I feel I must make a shaming confession. I have never read The Twyborn Affair. I know, I know. I’m finding it hard to read fiction at the moment but I sense I need to correct this oversight PDQ.