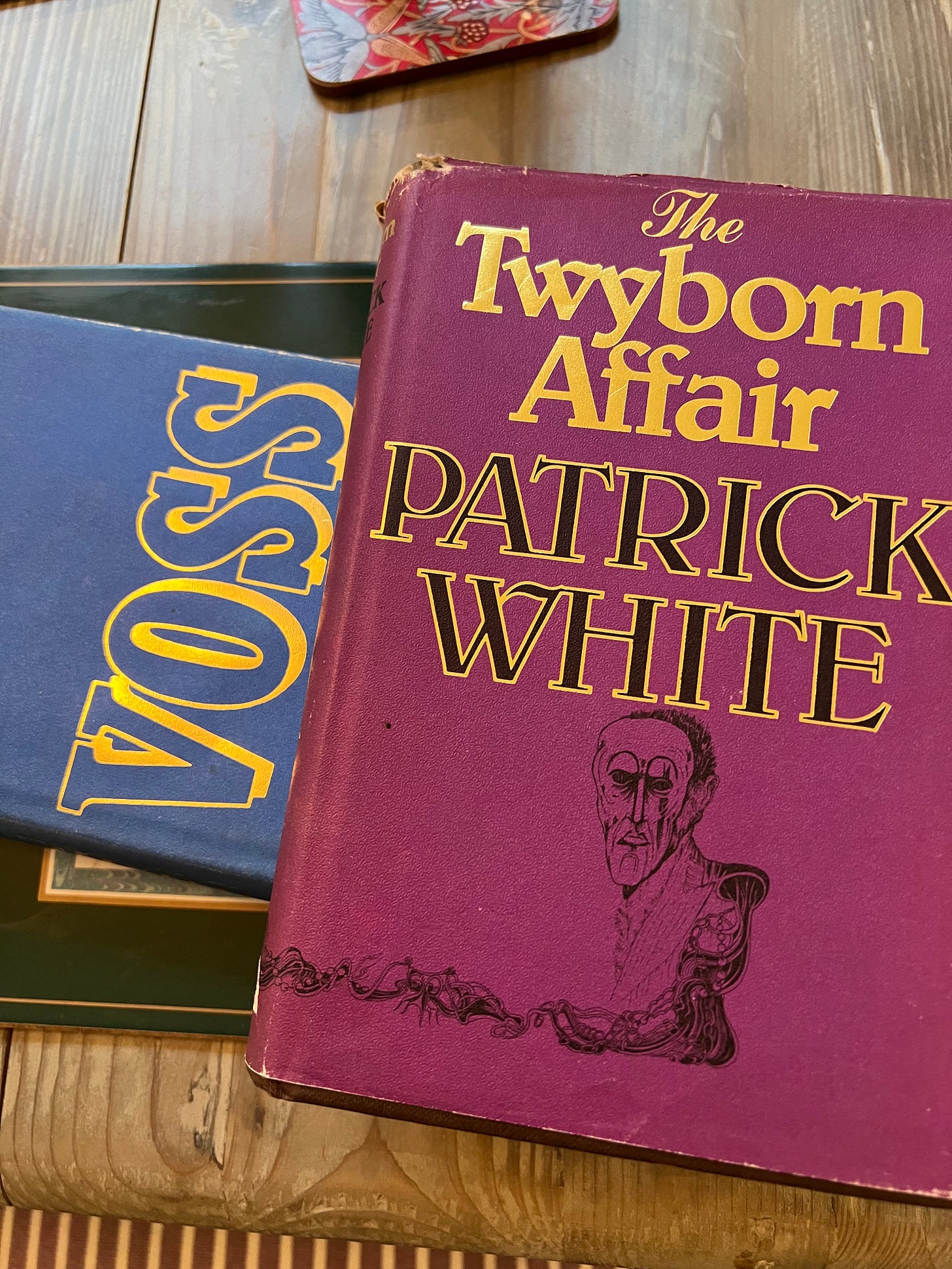

Last year, I set out to read all of Patrick White’s novels (and reread Voss and Riders in the Chariot), as well as his autobiography Flaws in the Glass, and the masterly biography by David Marr. Needless to say it’s an ongoing project!

I’ve just finished rereading Voss (1957), and knew to expect its poetry, metaphysics, brutality and linguistic complexity: Robert Macfarlane writes, brilliantly, that ‘words in White are so often acquitted of their usual obligations and left to pivot like compass needles looking for their lost norths’.1 (I’d forgotten about its simpler Jane Austen aspects, the irony and social comedy, which I realise now appear in all the novels).

Before Christmas, I read The Twyborn Affair (1979). I found it staggering.

I think the less you know about it the better. In Flaws in the Glass (1981), White was typically heretical: ‘Those who discuss the homosexual condition with endless hysterical delight as though it had not existed, except in theory, before they discovered their own, have always struck me as colossal bores’ (here I wonder what he’d make of the journalist at The Guardian who thinks or pretends that LGBT culture began with what he’s just watched on Netflix).2 In the early 1970s, when asked why he hadn’t written a novel with a gay character at the centre, White replied that homosexuality in fiction ‘is a theme which easily becomes sentimental and/or hysterical. It is, anyway, rather worn’.3

Whether or not you agree with these two provocations, between making them, the great and flawed man published what is arguably his masterpiece (Marr argues this), more towering, even, than Voss: it’s a monumental LGBT novel.

Patrick White, Voss, intro. by Robert Macfarlane (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1957; repr. London: Vintage, 1994), p. xi.

White, Flaws in the Glass (London: Jonathan Cape, 1981; repr. London: Vintage, 1998), p. 80.

White, quoted in David Marr, Patrick White: A Life (Sydney: Random Century, 1991; repr. Sydney: Vintage, 1992), p. 583.