Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958)

Or, Why I Should Have Left Holly Golightly Alone

Hello,

In last week’s newsletter on David Malouf’s wonderful Johnno, I had reason to mention Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

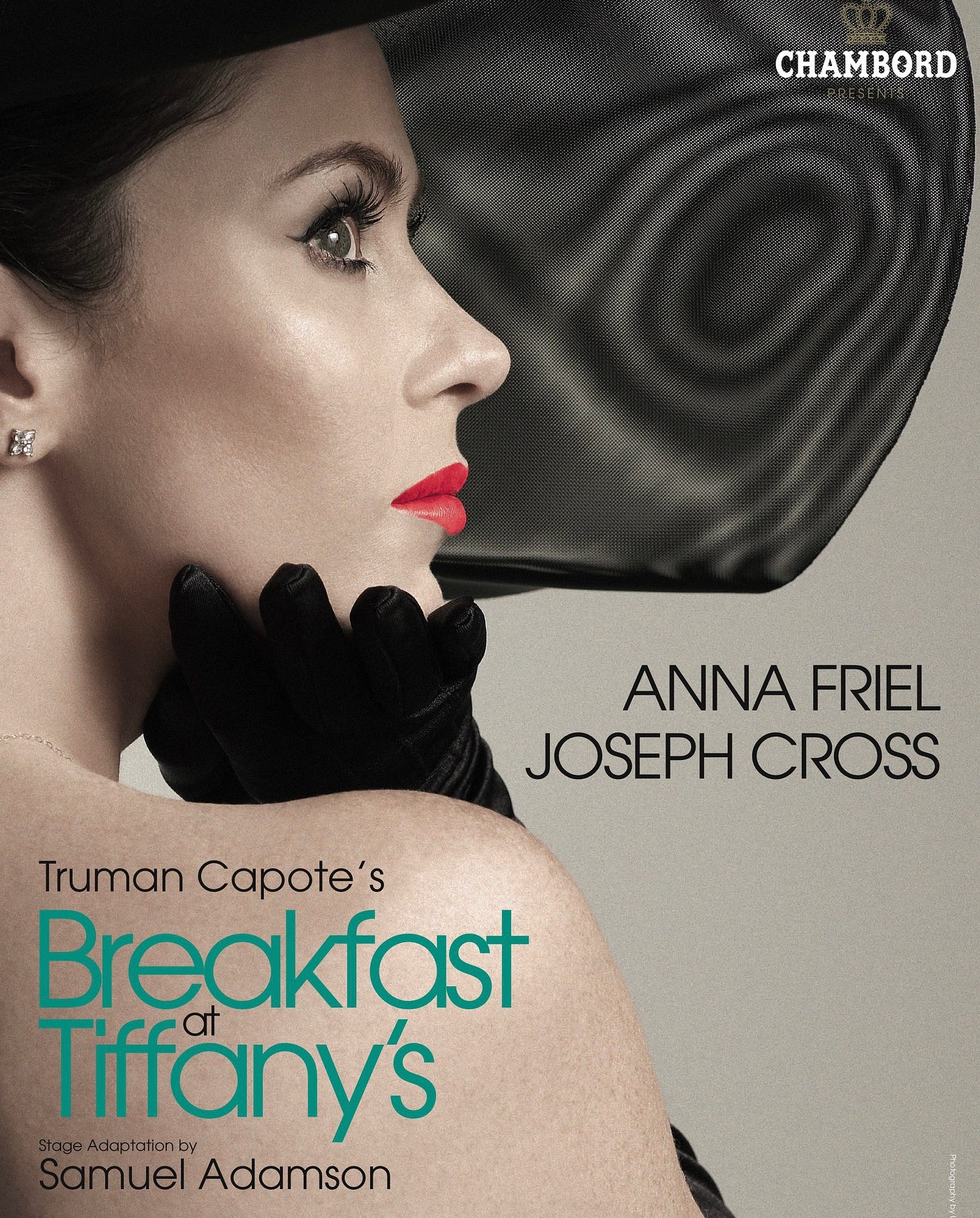

Over a decade ago, I adapted Capote’s novella as a play in London. It was a deeply unhappy experience – the only truly terrible time I’ve had working in the theatre.

I had planned this week to write about another novel, but in the days after returning Johnno to the bookcase, I found myself writing about Tiffany’s:

about how the famous 1961 film differs from the book;

about why I think it’s a book that doesn’t need to be adapted;

about how I made an error of judgement when I chose to do just that.

The theatre can be a place of delirious highs and mortifying lows. Happily, I’m well and truly over the low of Tiffany’s – proof of which, perhaps, is that when, thanks to Johnno, the figure of Holly Golightly re-emerged on my figurative fire escape, I was entirely unmoved, and began to write.

Tiffany’s doesn’t fit with my general aims for this newsletter. But after some toing and froing, and probably not enough polishing, I’ve decided to share these reflections.

I’m a bit disparaging about the novel (though I love it), the film (though the screenplay does something clever) and my stage version. As they say on other platforms, Might Delete Later.

Except this is going out to my lovely subscribers in an email.

Well, the book and movie can take anyone’s brickbats, and the theatrical gossip isn’t juicy. So, read on if you’re interested in my thoughts on the best place for Holly Golightly.

Sam

Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a deceptive novel. On the surface, it’s about what used to be called a good-time girl, the sparkling Holly Golightly, who enchants a young writer she calls ‘Fred’. But underneath, it’s a restless little tale without a happy ending about a call girl and a gay man who can’t work out where they fit in the world.

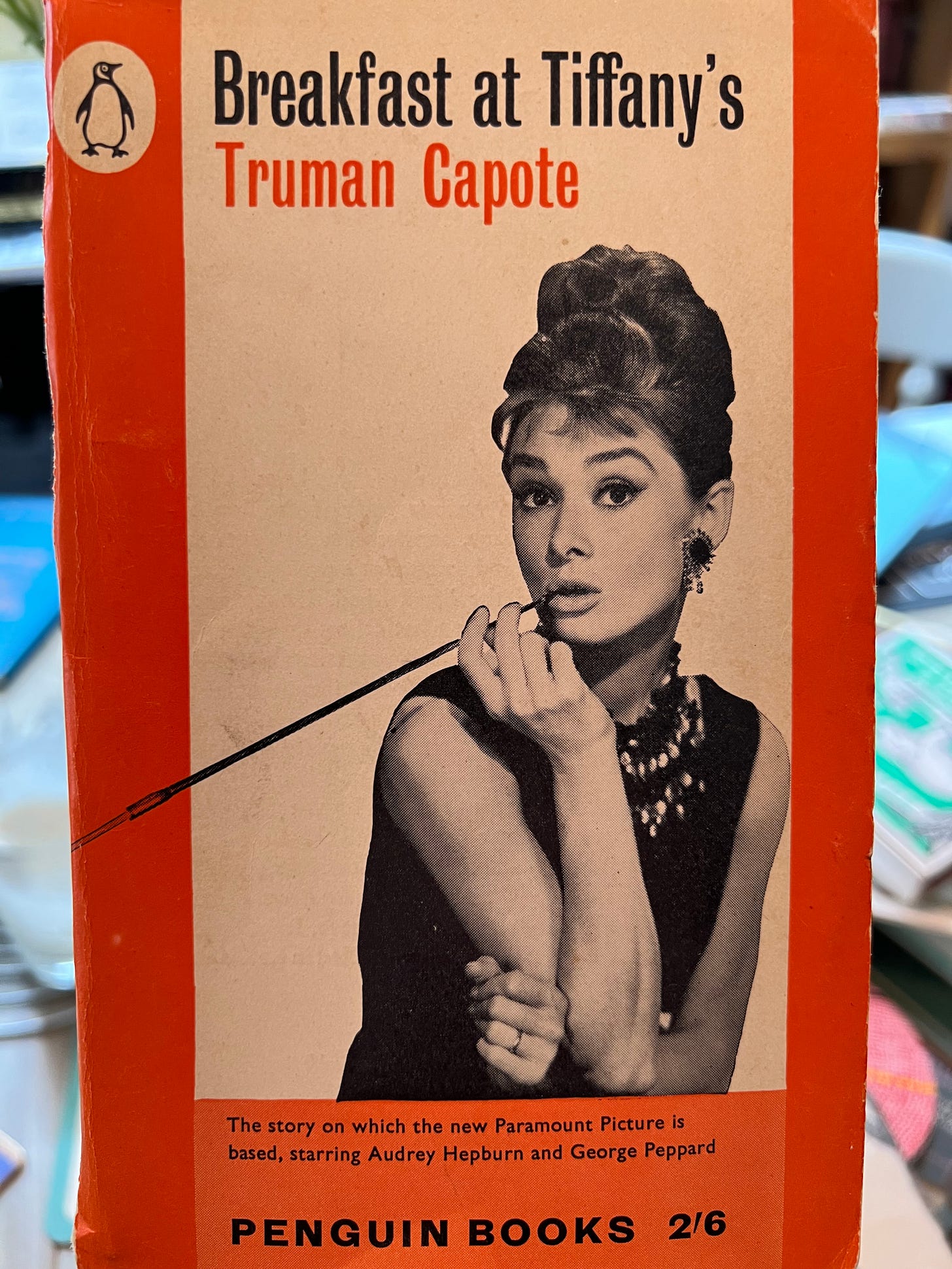

Despite Hollywood not being particularly faithful to it, and prudish about it, the screenwriter George Axelrod adapted it skilfully for director Blake Edwards. One radical and very shrewd thing he did was to make Fred, played by George Peppard, a gigolo. This provided the screenplay with its requisite naughtiness, and meant that pretty, pristine Audrey Hepburn could appear as Holly without the audience having, necessarily, to acknowledge that she is the story’s hooker.

You can watch the film and take what Holly says at face value: that she gets fifty dollars from men to go to the powder room to powder her nose. I prefer Capote’s Holly, who more obviously gets fifty dollars for services rendered, but Edwards and Axelrod’s Holly is unquestionably appealing, and Hepburn is irresistible.

The other thing Axelrod’s intervention did was to turn a queer novel into a straight movie. Capote’s Fred is gay – it’s one reason he and Holly can’t be together. When in 2009 I was asked to adapt the novel for a West End audience, I wanted to excavate this, since it’s a common enough predicament (or it used to be), and plays need predicaments.

In drafts of my adaptation, a worldly-wise Holly helps Fred to accept himself for who he is before she leaves him. But in the production, for – in my view – various commercial and I’m sorry to say homophobic reasons, Holly was Hepburnish and Fred’s homosexuality was suppressed even more than it was by Axelrod. Peppard was the quintessential all-American jock, yet he was a hundred times gayer than the West End Fred.

Thanks to Axelrod, who contrived a romance between Holly and Fred, people want Tiffany’s to be a boy-meets-girl fairy tale. But in the novel, the princess is a fraud and the mincing prince informs us, ‘[n]ever mind why’, that he once walked five hundred miles to visit a place called Nancy’s Landing.1

You don’t need to have read Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick to work out what went on there.

I’m wary of our culture’s readiness to pronounce novels dated; ‘problematic’ texts can be made more problematic by utterly hopeless ‘sensitivity readers’. Nevertheless, the author Daisy Buchanan once tweeted that growing up means realising Holly Golightly is a ‘massive asshat’.2 If you haven’t read Tiffany’s, do, it’s diverting, but you’ll have to face that its sexual politics are dated, and that Holly is on more than one occasion racist. Fred is deliberately unknowable and not particularly likeable. The tone is as sardonic as it is romantic, and the narrative is episodic and non-dramatic.

The London production in my adaptation failed artistically (it was a commercial success) for these and many other reasons. It was a miserable experience. Everyone was at cross purposes during rehearsals. Lies were commonplace. The talented actors were valiant, but the interminable preview period felt like a circle of Hell.

But hey, it was only a play.

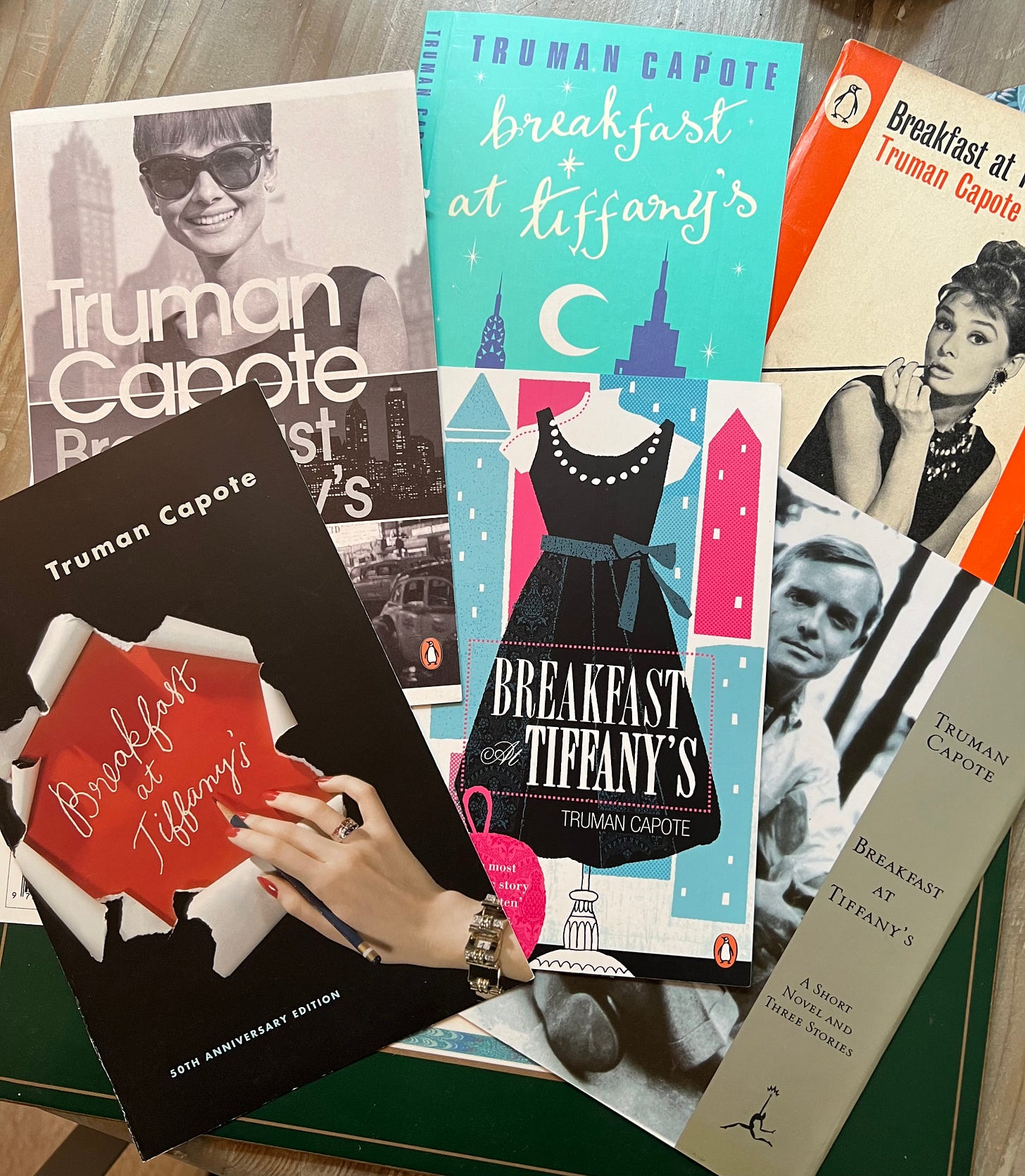

Before my adaptation (starring Anna Friel, a delight), Edward Albee’s musical version (starring Mary Tyler Moore) bombed on Broadway. Since my adaptation, Richard Greenberg’s adaptation (starring Emilia Clarke) bombed on Broadway, but had another life in London (starring Pixie Lott). Producers – it’s producers who drive this kind of theatre – just can’t leave Tiffany’s alone. ‘Find a star,’ they think, ‘and trust the title’.

What they don’t get – aside from the fact that the iconography of Hepburn’s Holly is unassailable – is that Capote’s Holly is elusive. There’s a marvellous On the Town-ish moment in the novel when Fred sees a ‘happy group of whisky-eyed Australian army officers baritoning “Waltzing Matilda”’ to her.3 Spin-dancing, she floats ‘round in their arms light as a scarf’. It’s perfect: the Australians are passing through, Holly is passing through, ‘Waltzing Matilda’ is a ballad about an itinerant bushman who’d sooner kill himself than be caught alive. Holly is an enigma, paradoxically sophisticated and provincial, and Axelrod (helped by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s ‘Moon River’) was true to this until in his climax he yoked her to a man. Really the point of her is that she keeps floating away – and the men (though not the Australians) can’t stand it. Her mailbox card reads ‘Miss Holly Golightly, Travelling’, and this nags Fred ‘like a tune’.4

To paraphrase the lyrics of a nagging tune, the film is kinda likeable. Yet however stylish it is, it Hollywoodizes Holly and Fred by reshaping her, Pygmalion-like, from a good-time girl into a good girl, and by heteronormalising him.5 There is also the indefensible matter of Mickey Rooney, in yellowface as Mr Yunioshi. A better film version is Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s Mistress America, which recasts Fred as a woman, and manages to be quite charming. Yet, frankly, still quite annoying.

Some literary characters should stay in our imaginations (see also: Cathy and Heathcliff). Holly doesn’t need to be on stage – or even on film. We really don’t need to suffer ghastly Mickey Rooney for the sake of lovely Audrey Hepburn. We can watch Sabrina or Charade instead.

After all these years, I don’t mind being a theatrical footnote in the company of Edward Albee and Richard Greenberg.

I used to regret my involvement, but like Holly, you keep travelling.

My biggest mistake was to say yes in the first place.

Yes, the best place for Holly Golightly is between the covers of Capote’s book, in his exquisite clear-as-a-country-creek sentences, in the far-flung part of the world to which she delivers herself at the end, never to be seen again by her gay best friend.

Till next Sunday’s book …

Truman Capote, Breakfast at Tiffany’s (New York: Random House, 1958; repr. London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 95-6.

Daisy Buchanan, @NotRollergirl (1 January 2014) https://twitter.com/NotRollergirl/status/418356546389938176

Capote, pp. 19-20.

Capote, p. 16.

It’s fascinating that another literary character played famously by Hepburn also lost her independence – because Alan Jay Lerner had played Pygmalion to Pygmalion for My Fair Lady and yoked Eliza Doolittle to Henry Higgins. Never forget Bernard Shaw’s magnificent climactic stage direction for Eliza, which is surely up there with Ibsen’s door slam in A Doll’s House for Nora: She sweeps out. (This on the back of her equally magnificent exit line: ‘What you are to do without me I cannot imagine’.) Arguably all these female characters – Nora, Eliza, Christopher Isherwood’s Sally Bowles, Holly – became, in some of their after-lives, dress-up dolls for male adaptors. But that’s another newsletter.

Re. the collective noun, according to the writer and director Mark Rosenblatt, it's a breakfast of Tiffanies. Chapeau!

Fascinating. You're completely right about the fact that Holly is and should remain elusive - which is why embodying her on stage and screen is fatal. See also Jay Gatsby.