(The True History of) Jack Maggs

A dramatic rectification by Mercy Larkin in a play by Samuel Adamson based on Jack Maggs by Peter Carey in postcolonial response to Great Expectations by Charles Dickens and a 'greater truth' not told

Hello,

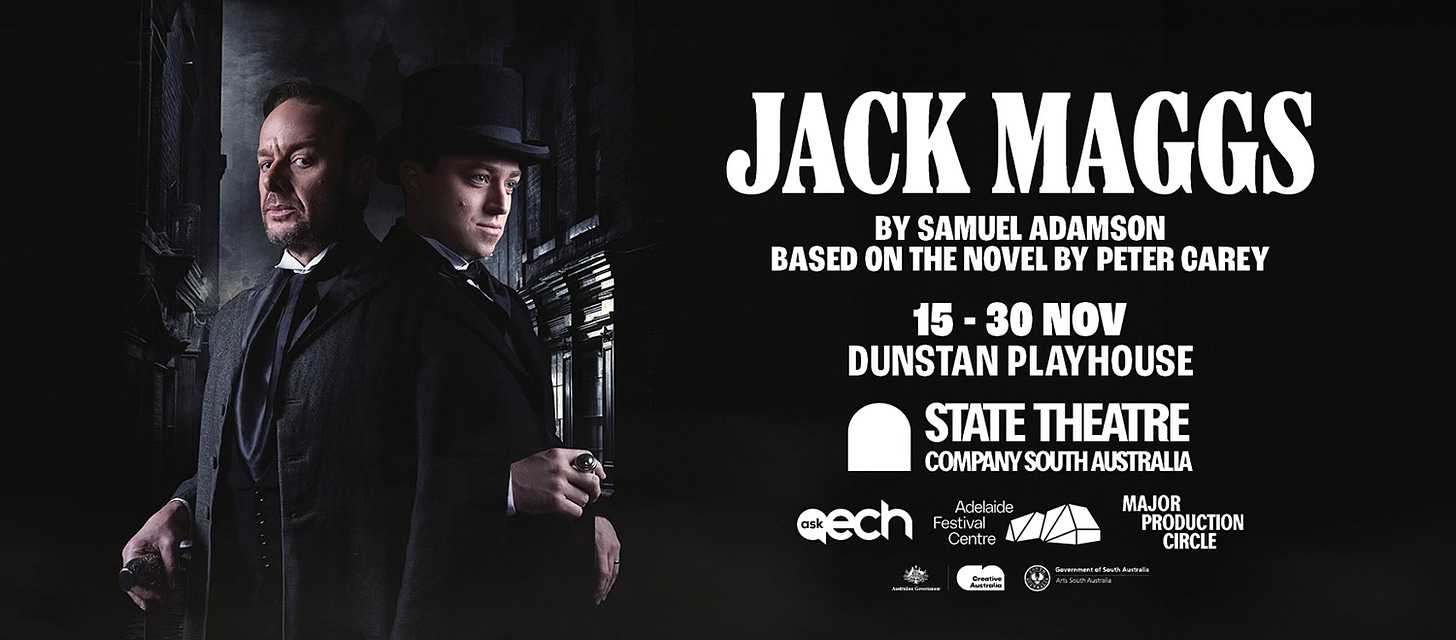

This Friday 15 November, my new play Jack Maggs, based on the wonderful 1997 novel by Peter Carey, opens at the Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre, in a production by State Theatre Company South Australia.

If you’re in Adelaide, I hope you can come along; it’s directed by Geordie Brookman and designed by Ailsa Paterson, and has a marvellous cast led by Ahunim Abebe as Mercy Larkin, Mark Saturno as Jack Maggs, James Smith as Tobias Oates, and Jacqy Phillips as Ma Britten.

It also plays in Canberra.

If you’re not in Adelaide or Canberra, the play is published by Faber Drama and is available here (Amazon UK) and here (Allen and Unwin Australia).

Carey’s story is a great yarn, and I wrote about it here:

Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs (1997)

Hello, In Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs, set in London in 1837, there’s a terrific sequence in which the house at Number 29 Great Queen Street, where the title character works as a footman, is declared by a doctor to be in a state of quarantine thanks to a contagion.

In addition, with thanks to State Theatre Company South Australia, here is my programme note for the premiere production. The photographs are by Claudio Raschellá.

To engage with Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs – with its nineteenth-century London setting, its politics, its humour, its anger, its gloriously eccentric story about a convict with identity problems – you don’t need to know anything about two things that inspired it: the life of Charles Dickens and Dickens’s 1860-1 masterpiece Great Expectations. Like all good stories, it works on its own terms.

Nevertheless, Jack Maggs came about because Carey was ‘mad at Dickens for giving my imaginary ancestor a bad rap’ – that ancestor being Magwitch, the convict who in Great Expectations returns from New South Wales to England, where he reveals himself as the benefactor of the novel’s narrator Pip. According to Carey: ‘I had this notion that there was a real Magwitch, and Dickens had known a more complicated and greater truth and had not told it.’

So, in 1997, Australia’s great trickster-novelist told that ‘truth’, and in doing, raked Dickens over the postcolonial coals.

To the postcolonial reader of Great Expectations, Magwitch is a one-dimensional and sentimental fellow. He has no crisis of identity upon his return to the England that banished him. With the focus of the story upon Pip’s rite of passage, Australia is a vague netherworld, with little in the text to suggest the tortures the convict must have endured in the penal stations of New South Wales. In Jack Maggs, Carey disturbs all this. The rite of passage belongs to the convict, now named Jack Maggs, a man of immense complexity and integrity. The Pip figure is deliberately one-dimensional. The horrors of Moreton Bay, and of Jack’s childhood in London, are depicted in unsparing detail. Perhaps Carey’s greatest coup is his novelist character Tobias Oates. Much about this mesmerising but amoral young man on the make is pilfered from the life of Dickens – an exquisite irony in a story about the ethics of storytelling and the slipperiness of ‘truth’.

The UK (not to mention UK theatre) rarely faces its invasion of Australia or the cruelties of transportation. Jack Maggs is an important corrective to this. Although only the last of its 328 pages is set in Australia, its republican politics and larrikin irreverence make it a profoundly Australian novel. I’m thrilled Peter Carey has allowed me to pilfer from him and turn into a play.

Except it’s not my play, it’s Mercy Larkin’s. She is your storyteller – or, to use the old Australian slang, your magswoman. She willingly admits to having once or twice stretched history to suit her own dramatic ends, but otherwise everything she says in her True History of Jack Maggs is true.