Hello,

In Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs, set in London in 1837, there’s a terrific sequence in which the house at Number 29 Great Queen Street, where the title character works as a footman, is declared by a doctor to be in a state of quarantine thanks to a contagion.

This is a sham: the doctor is not a doctor, and there is no contagion.

There is, however, a returned transport in the house. Number 29’s other servants have discovered that the footman Jack Maggs is no servant but a ‘bolter’ – an ex-convict from New South Wales.

Granted a conditional pardon in the Colony, Jack has made a fortune making bricks from Sydney clay, and has returned to England to reunite with the resident of the house next door to Number 29, a Mr Henry Phipps. On the day Jack was transported from his beloved England, Phipps, then a little orphan, gave the manacled and starving criminal some food. For this exquisite kindness, emblematic of the best of England, Jack has supported Phipps from Australia, educating him and filling his house at Number 27 with expensive rugs and paintings. The prospect of meeting Jack again, however, has sent Phipps into hiding: made a gentleman by a convict, he never expected his Australian benefactor to return. Jack is determined to find the man he considers his son, and so has become embroiled with the household at Number 29. But the longer Jack stays in England, the more he risks being hanged: a convict is transported for the term of his natural life.

It’s thanks to the sham doctor that Jack’s secret is known. He is a famous young novelist, Tobias Oates, a man fascinated by mesmerism (all the rage in late-Georgian England) – and the traumatised Jack has confessed to his past under the influence of Tobias’s ruthless mesmeric techniques. The convict needs the novelist’s help to find Phipps; the novelist, afflicted with a severe case of Second Novel Syndrome, needs a good story. So, to contain Jack’s secret within Number 29, Tobias, a theatrical fellow, disguises himself and illegally quarantines the house. He thus has more time to extract from Jack juicy plot and character details about the brutalities of transportation for his Second Novel; while Jack is safe as the household’s imprisoned servants are prevented from alerting the authorities of his true identity.

Jack Maggs had precisely what he had wished: the dike was plugged; the gossips were contained. But as he set out to secure his territory, the convict’s heart fell prey to a new anxiety – a blood-dark feeling in his gut – that he had become the captive of someone whose powers were greater than he had the wit to ever understand.1

If some of this sounds like Great Expectations, that’s because Jack Maggs is Carey’s answer to Charles Dickens’s great novel. In his own words, the Australian Carey was ‘mad at Dickens for giving my imaginary ancestor a bad rap’ – that is Magwitch, Dickens’s convict, the benefactor to the orphan-hero Pip. ‘I had this notion that there was a real Magwitch, and Dickens had known a more complicated and greater truth and had not told it’.2

So Carey told it, taking by the throat the iconic Victorian storyteller, and arguably his most iconic story, and giving them a thoroughly Australian throttling.

Audaciously, Carey does not simply tell Magwitch’s story, but instead uses Great Expectations as the basis for a new story about a convict far more complex than Dickens’s sentimental creation. Even more radically, he takes Pip – whose great expectations Great Expectations is about – and reimagines him as the abominable Phipps, a character deliberately less complex than Dickens’s orphan. The story becomes about the convict’s great expectations, and Pip transmogrifies into the worst of England, the epitome of the horrors of Empire, a decadent fool who, unlike the flawed but loveable hero of Great Expectations, rejects his convict benefactor entirely. Jack’s great expectations are dashed because – Carey’s words again – he realises that ‘his beloved adopted son and his torturer are the same person’. It’s a classic piece of twentieth-century postcolonial ‘writing back’ – on a par with Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (Jane Eyre) and J.M. Coetzee’s Foe (Robinson Crusoe).

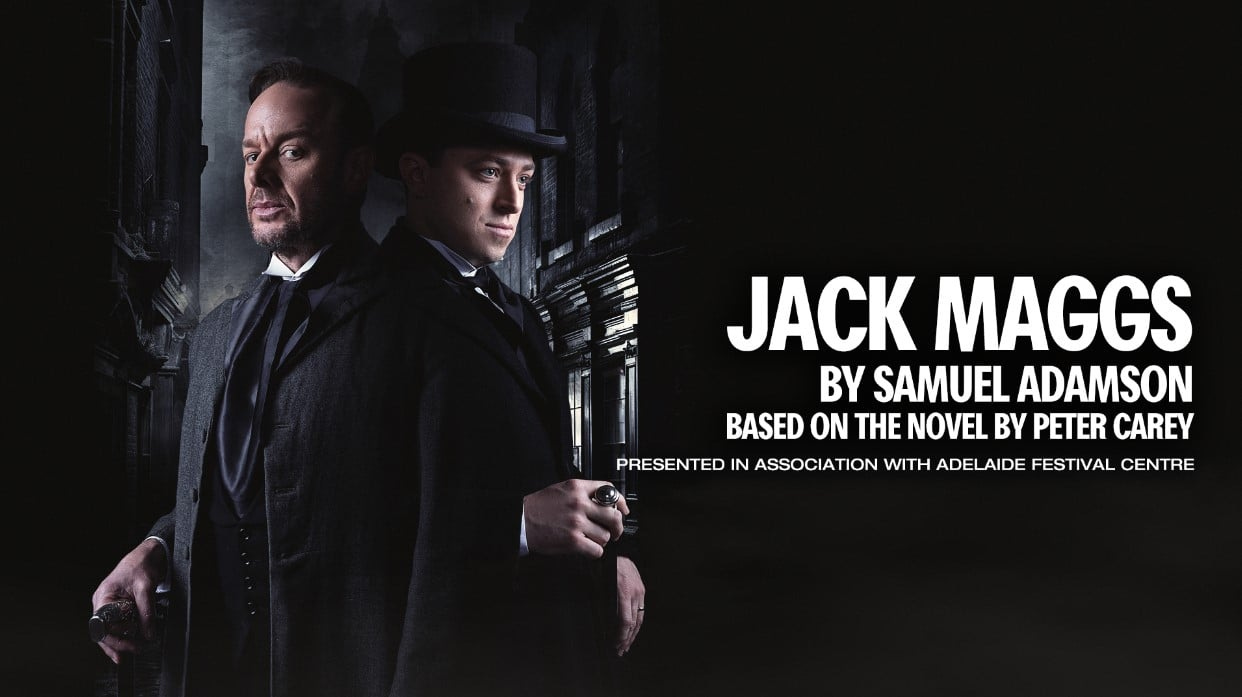

When in 2019 I first started work on my adaptation of this wonderful novel for State Theatre Company South Australia, the sham contagion episode seemed to me impossible to dramatise. It comes at a point in the story when, for a play – with its two hours’ traffic – things need to rattle on, and I wondered how, without Carey’s vivid and contextualising prose, I could make a domestic quarantine convincing and accessible to a twenty-first-century theatre audience.

Then, of course, something happened to all of us, and the aspect of the novel I’d thought the most esoteric and historically remote – a lockdown as the writer-trickster Tobias’s solution to Jack’s problem – became the most relatable thing in the book.

It was a lesson: we can never be sure when something that seems to us dated or irrelevant in a work of literature might, without warning, speak to our times.

Like Tobias, Carey is a trickster – one of literature’s greatest. Jack Maggs is popular in English departments because of its sly intertextual connections not just to Dickens’s work, but to his life: it takes a close reading to see just how much Tobias Oates and Dickens share. Tobias has a loveless marriage – as Dickens did with his wife Catherine Hogarth – and the plot hinges on Tobias’s relationship with his sister-in-law. This is a bold imagining of Dickens’s relationship with Catherine’s sister Mary Hogarth. Much is known about Dickens’s obsession with mesmerism, his love of theatre, his connections to Australia (though he never visited). Little is known about his relationship with Mary, or Mary herself, except that she was probably the inspiration for The Old Curiosity Shop’s Little Nell, and died at the age of 17 on 7 May 1837. This is the exact day that Tobias’s sister-in-law dies in Jack Maggs.

The trickster Carey (or to employ the old Australian word he employs in the novel, the magsman) loves to play games with the reader, and to disguise things like this with dazzling red herrings and sleights of hand – here, he calls Tobias’s wife (i.e. the Catherine character) Mary. But by dramatising a relationship between a Dickens-like novelist and his sister-in-law, Jack Maggs is the literary equivalent of Claire Tomalin’s The Invisible Woman, which assembles the scant available evidence to argue Dickens’s extra-marital affair with Nelly Ternan.

It’s a book, then, that both honours Dickens and does him like a kipper. It appropriates someone else’s story to ask tough questions about appropriation: who gets to voice whose experience? Fearless in its interrogations of the brutalities of Empire, it faces the invasion of Australia and the inhumanity of Britain’s system of transportation to tell the ‘greater truth’ that Dickens ignored.

If you haven’t encountered it and you love Dickens (and to be clear, Carey loves him – his very irreverence towards him is Dickensian), do seek it out. It’s a postcolonial reckoning, and also a great yarn.

And if you’re in Adelaide, please come to the play! I’m excited about bringing Carey’s masterpiece (one of several masterpieces) to the stage. Aside from the fact that bringing anything to the stage is exciting (and scary), it means I have an excuse to read it again and again.

Till the next book …

Peter Carey, Jack Maggs, (London: Faber, 1997; repr. 2011), p. 147.

Carey, quoted in Mel Gussow, ‘An Australian Novelist Takes Another Look at Dickens’s Inimitable Convict’, New York Times, 25 May 1998, Section E, p. 9.

Loved this review, Sam. Not read this book (and not a huge fan of Dickens, probably due to being forced to read 'Dombey and Son' as an undergrad, which was handy as a doorstop but didn't really thrill me as a work of literature), but I love the comparison you make with Jean Rhys' 'Wide Sargasso Sea'. I think it's really interesting when a writer takes an earlier text and does something really interesting with it. Sadly, I am not in Adelaide this November, otherwise your adaptation looks thrilling! :)

This is great. I think I read it when it came out and will see if I can dig it out and put it on my TBR pile. I think I will get much more from it now, thank you!