Hello,

Today – in what is surely an instalment in a series of posts about writers named Penelope – I discuss Penelope Mortimer’s superb The Home (1971).

I hate to be that Londoner who tells you that if you’re in London you should find forty quid to be a groundling at the Bridge Theatre’s Guys and Dolls – but I am that Londoner. I’ve never been part of a happier theatre audience.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend.

Sam

A section of her was composed of the ability, the necessity to part; the inevitability of parting.1

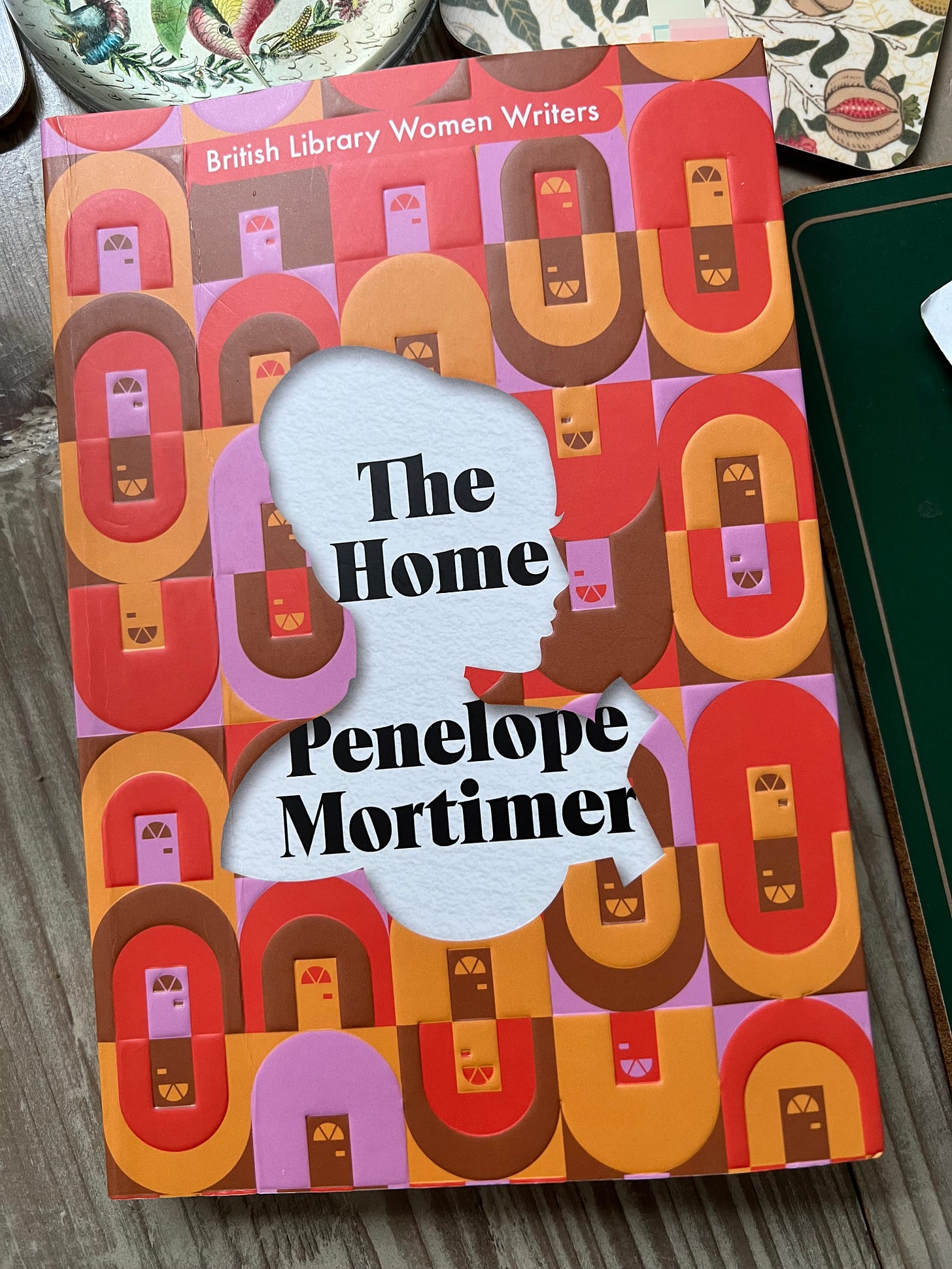

I’d never heard of Penelope Mortimer’s The Home until the other day when I drifted into Foyle’s in Charing Cross Road and noticed it on a display table in their fiction section, in a new 2023 edition published by the British Library. On an impulse, I bought it, started to read it on the 188 home, and was riveted. (There’s a sting in this tail/tale: see below.)

I love novels about families, about London, about the endings and beginnings of relationships; and about the loneliness, big-heartedness and muddled acts of self-preservation of the human beings that another Penelope, Penelope Fitzgerald, called ‘exterminatees’.

The Home is about all these things, so frankly I was in heaven.

I also like novels about the middle class, and this being England, I feel obliged to say that Mortimer’s novel is very middle-class. This is a world of moneyed Londoners, boarding schools, Wimpole Street doctors, English expats in Paris writing ‘film script[s] of the life of Kafka’, painters ‘in the Francis Bacon style’, regular travel abroad, and stiff-upper-lip ladies with flats behind the Albert Hall.

The universal is in these specifics, because Mortimer’s writing is so good: ironic, allusive, tragicomic, and – with its omniscient narrator who is discriminating about what to reveal about the characters’ inner lives, and when to reveal it – deliciously sly.

The story opens with its 50-something protagonist, Eleanor, leaving her husband, the father of her five children, and driving with her youngest to her new home, a large house in St John’s Wood. Thereafter, as the children come and go, it explores perennial questions, particularly as they apply to women:

what is Home?

can you be an individual, and happy, if you’re in a relationship – and/or if you’re a mother?

can you be contentedly single?

can lovers be friends?

what in our make-up do we owe to our parents, and are we even capable of recognising these characteristics, and if we are, can we do anything about it?

(I tend to see Ibsen in everything, but these are some of the questions Nora Helmer asks when she leaves her marriage in A Doll’s House.)

As it’s 1971, the idea of a divorce for Eleanor has the whiff of scandal about it, but only a whiff. This is a liberal English family: tolerant of difference; aware of, and mildly troubled by, its own complacency; presided over by a pair of Austenesque matriarchs who look upon their children and grandchildren’s antics with a mixture of resignation and indifference. There’s a lot of extra-marital sex. There’s a gay son and a hippy daughter. There are drugs, alcoholism, hasty register-office weddings, pregnancies outside marriage, and a slight tussle between medication and psychoanalysis as the treatment for depression.

The only thing that really pins it to its period – aside from several ageing 1970s Don Juans and all the wonderful London detail (pubs closed in the afternoons, revolting food, long-haired teens reading Catch-22) – is that Eleanor doesn’t work.

Yet you feel that were she to have a career, her tragedy – her loneliness – would remain. Via her exploration of the tension between the matriarchs’ creed of ‘not making a fuss’ on the one hand, and Eleanor’s need to articulate her pain on the other, Mortimer makes loneliness her timeless theme. Eleanor’s pain stems from separations from children and from lovers: as the quote above indicates, ‘parting’ is a key word in this book. All families and friendships fracture, and Mortimer poignantly shows that things which seem mere fractures, such as everyday farewells, are often in fact irreparable breakages, final goodbyes to the old ways of relationships.

Eleanor is too sensitive – too big-heartedly motherly? – to claim her right to the distress these partings cause. So Mortimer’s narrator does it for her. At one point, Eleanor’s daughter Cressida begins a relationship with Eleanor’s ex-lover Ellis:

It was the hideous situation of finding herself in competition with Cressida – could it really be as crude as that? – that so immensely distressed her. And, worse, the fact that she could never be in competition with Cressida, but must give way gracefully, with love, pretending that nothing was being taken from her. Ellis’s contemporary, Cressida’s mother, she felt that she must give them her blessing and let them go. As always, anger, unrighteous and irrational indignation, was not available to her.

Grace, love, loss, individuation, pretending, blessing, letting go – these are the universal human concerns of each of The Home’s twenty-seven short chapters.

And just look at the artfulness of the narrative omniscience, the way anger is ‘not available’ to Eleanor. Isn’t that recognisable? It’s impossible not to empathise. When Eleanor’s teenage son says to her, ‘I don’t see why you can’t be more philosophical’ (about her husband’s new young girlfriend), all Eleanor can do is repeat the word philosophical ‘as though she were being trained to speak’. You take the teenager’s point, but you also want to scream with ‘unrighteous and irrational indignation’ on his mother’s behalf.

Eleanor’s need is to say out loud to the people she loves, I’m sick and I need help. I won’t tell you if she manages it; suffice to say that her journey involves a series of superb set-pieces – including a dinner to make anyone who’s ever behaved a little badly at a family gathering blush – that are moving and funny and true.

The British Library edition of this wonderful and (I think) long out-of-print novel is part of the new British Library Women Writers series, which in the publisher’s words ‘is a curated collection of twentieth-century novels by female authors who enjoyed broad, popular appeal in their day’. It’s been produced with love and care. There’s gorgeous cover art by Sinem Erkas, a handy guide to the key events of the early 1970s, a short biography of Mortimer, a Preface, a Publisher’s Note, and a very interesting Afterword by Simon Thomas.

The sting in this tail/tale is that in my view, no one should buy the 2023 edition as I did. Instead, they should find an old edition in a second-hand bookshop, on Internet Archive, in a local library, or indeed in the British Library itself.

I’ll explain why next week: I loved reading The Home so much, and something in it was so fascinating to me, that I have to write about it again, and express my exasperation that the British Library, of all places, is susceptible to the bloody modern scourge of sensitivity readers.

Until then …

Thanks for subscribing.

Update. Follow the link for Part Two:

Penelope Mortimer’s The Home Part Two

I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Penelope Mortimer, The Home (1971; repr. London: The British Library, 2023), p. 103. (The British Library gives the date but not the publisher of the first edition. It was London: Hutchinson.) Subsequent quotations are from pp. 24, 46, 81, 101, 104, 175.

Loved this review, Sam! I haven't come across this novel (or writer) before, and now I can't wait to get hold of a copy - thanks! : )