Penelope Mortimer’s The Home Part Two

Content warning: content warnings, publishers in their sensitivities, and queerness

I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

This week I discuss Penelope Mortimer’s The Home for a second time: I make the case that the British Library reissue should contain every word Mortimer wrote. If you disagree with me, please let me know. I reveal plot points and the ending.

If you’re in London: Dancing at Lughnasa at the National is so beautifully paced and acted and danced and the rest of it that I could have stayed in my seat and watched the whole thing again.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend,

Sam

In the theatre, content warnings are now common.

Sometimes, they’re absurd and patronising: at Theatre Royal Stratford East recently, audiences were warned – of a production of Much Ado About Nothing, no less – that Shakespeare’s ‘themes are not performed on the stage, but are within the writing and the script’.1 The Royal Court does things elegantly: on the booking page for Danny Lee Wynter’s BLACK SUPERHERO, it provides links to ‘Content Warning’ and ‘Self-Care’ guides for those who need them.2 I like the way Chicago’s Steppenwolf does it: they don’t ‘offer advisories about subject matter, as sensitivities vary from person to person’, but ask anyone who has questions or concerns about content or stage effects to contact the box office.3

Some people need and/or appreciate content warnings. If you don’t or you’re triggered by them – and I think many people are; the muddled Stratford East example is pretty triggering – then on the whole it’s easy enough to shrug them off.

The week before last, I encountered what amounts to a content warning in a novel – the first time this has happened to me. This was the ‘Publisher’s Note’ on p. xi of the British Library’s 2023 reissue of Penelope Mortimer’s The Home (1971), which I wrote about last Sunday.

Mortimer’s novel is part of a laudable project called British Library Women Writers, ‘a curated collection of twentieth-century novels by female authors who enjoyed broad, popular appeal in their day’.4 I assume every title in the series includes the Publisher’s Note, which contains this sentence:

There are many elements of these stories which continue to entertain modern readers, however in some cases there are also uses of language, instances of stereotyping and some attitudes expressed by narrators or characters which may not be endorsed by the publishing standards of today.

It goes on:

It is not possible to separate these stories from the history of their writing and as such the following novel is presented as it was originally published with a few minor edits only.

On the Content Warning Continuum, this sits closer to the Stratford East extreme than the Steppenwolf, and giving it my grouchiest reading, its implications are unfortunate: that today’s publishing houses are society’s moral arbiters; that readers are incapable of putting fictional writing into its historical context by themselves; that readers are incapable of putting fictional narrators and characters into their stories’ context; and that fictional narrators and characters must be held to some Pollyannaish human ideal.

I read the Note after I’d read the novel itself, found it triggering, and shrugged it off.

But then it began to gnaw at me, because in any reading, grouchy or otherwise, the claim that the text is ‘presented as it was originally published’ is ludicrous if the text has been subject to ‘a few minor edits’.

The Home spoke to me and touched me; in my view it’s a mini-masterpiece. So I don’t think it’s unreasonable of me to want all of it, every single word that Mortimer employed in 1971 to create her art.

As I discussed last week, the novel is set in London in 1971, and is about a lonely woman named Eleanor who leaves her husband. In the words of Daphne Merkin concerning another Mortimer novel, it is a ‘witty if often bleak […] dissection of the glitches – the unbearable muddles – that regularly occur in the most intimate of relationships, between mothers and their children or between husbands and wives’.5 One of the most intriguing things about it for me is its queerness. Eleanor has a teenage son, Philip, and four adult children, one of whom, Marcus, is queer – ‘queer’ is the word used for homosexuality throughout, with different connotations according to the context.

Marcus’s queerness is both the point and beside the point in all the scenes in which he features. Sometimes his homosexuality blends with the world and appears unexceptional; sometimes it clashes with the world’s heteronormativity, and a consequence is homophobia.

Less obvious, so even more intriguing, is a lesbian character who appears at the story’s edges and is pivotal to its climax. It’s possible to give The Home’s ending a very queer reading and argue that Eleanor, having given up on men – ‘gross in their habits, obsessed by sex, deceitful, vain and, worst of all, little boys at heart’ – begins a relationship with this lesbian; begins, that is, a life as non-heteronormative as her son’s.6

Every instance of queerness in this novel, or any novel, is significant to the LGBT reader interested in gay culture and history – and to any reader interested in anything. ‘To queer’ is to confound or to subvert: all readers of stories are hungry for surprise and subversion, otherwise every literary character might as well be Pollyanna.

After I read the Publisher’s Note, I read the Preface, and my sense that I’d been short-changed by the British Library began to grow. In keeping with the apologetic tone of the Note, the Preface is concerned about ‘[t]he instances of almost casual homophobic language used by Mortimer [which] feel jarring to the modern ear but reflected the attitudes of British society at the beginning of this decade [the 1970s]’.7

For three reasons, I think this is unnecessarily jittery. Firstly, as I’ve illustrated, The Home is a queer novel – and queerness is not a monolith. Secondly, it’s not Mortimer’s homophobic language but her characters’ – the kind of distinction our culture seems increasingly loath to draw. Thirdly, bring on the discomfort and offence if the fiction tells me something about the human condition.

The fact is, Philip, who’s ‘just fifteen’, does not like Marcus and is a bit homophobic.8 (Whether his homophobia and his dislike are the same thing is debatable: it’s also a fact that Marcus can be overbearing, selfish and pretentious; and he does something to Philip that any sibling would have a right to be pissed off about.)

I don’t know if Philip’s homophobia has been softened by the British Library or not, because they don’t declare what their edits are. I do know that some fifteen-year-old boys are homophobic – they were in 1971, and they are in 2023. Philip’s attitude ‘may not be endorsed by the publishing standards of today’, but I don’t care about that because as a gay man I find his homophobia not only historically interesting but true to life.

Mortimer holds the mirror up to nature. No one should apologise for that.

Given all this editorial unease, my inner Carrie Bradshaw couldn’t help but wonder: do any of the British Library’s ‘minor edits’ involve the novel’s queerness?

It took me about three minutes to establish that one does.

The 1971 edition of The Home is on Internet Archive, and acting on my hunch, I searched the text for the word ‘queer’. In Chapter 17, there’s a sequence between Eleanor and Marcus set in a ‘really filthy, sordid English pub’.9 Marcus, who lives in Paris with his boyfriend Marcel, looks around the pub and cries, ‘One forgets how gay the English are’. Near to them, at the bar, is the ‘Dykey’ girl central to the novel’s ending, with an older woman signified as lesbian because she is ‘dressed in jeans and a shirt’. Over their brandies, Marcus asks Eleanor about an unreliable ‘Gaelic knight’ she fancies who has stood her up one too many times.10

On page 142 of the 2023 edition, the text reads:

‘Oh, Marcus …’ She mocked him, conscious that the woman and the girl were talking about him. ‘Yes, I fancied him.’

‘And you think you and he would have … fitted?’

‘Oh, I don’t know! At least the … mechanism … is right.’

‘Darling Mother, what you want isn’t mechanism. It’s love.’

‘It would be nice to have both. You and Marcel have both.’

On p. 163 of the 1971 edition, the same passage reads:

‘Oh, Marcus …’ She mocked him, conscious that the woman and the girl were talking about him. ‘Yes, I fancied him.’

‘And you think you and he would have … fitted?’

‘Oh, I don’t know! At least the … mechanism … is right.’

‘Darling Mother, what you want isn’t mechanism. It’s love.’

‘It would be nice to have both.’

‘It would be nice to be the Aga Khan. Particularly a queer Aga Khan.’

‘You and Marcel have both.’11

This is a fascinating sequence for many reasons. The easy way the heterosexual mother and her gay son discuss love and lovers, and the way the mother considers as entirely natural both Marcus’s relationship with Marcel, and the campness of his diction (‘Darling Mother’, ‘a queer Aga Khan’) are remarkable for being so unremarkable.

The sequence also foreshadows the ending in which, in the queer reading, Eleanor rejects men like her unreliable Gaelic knight for the lesbian girl she notices here at the bar. Everyone’s gaydars, including Mortimer’s, are finely tuned.

Of course one can see why the passage gave the publishers pause. But if the text had read simply, ‘It would be nice to be the Aga Khan’ would it have escaped their blue pencil? What Marcus says is outrageous, Western, and privileged. But Marcus is all these things – and to any gay reader, his rhetorical flamboyance is also recognisable as a kind of verbal drag, as high camp, as what Christopher Isherwood in The World in the Evening (1954) calls an expression of ‘what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance’.12 Note that Marcus doesn’t say the Aga Khan is queer, but that he, Marcus, wouldn’t mind being a queer Aga Khan: ‘You’re not making fun of it’, in Isherwood’s words, ‘you’re making fun out of it’.

Given the collision of sensitivities, given – to quote Steppenwolf again – that ‘sensitivities vary from person to person’, and given the provision of the content warning/Publisher’s Note, surely the thing to do is to let readers read what Mortimer wrote, and interrogate it for themselves according to their own values and beliefs.

With Marcus’s line cut, it’s hard for me to avoid the feeling that the ‘problematic’ and/or ‘offensive’ thing for the British Library is the word ‘queer’. I wondered if I’d find an unnecessary softening of Philip’s homophobia; what I found was an editorial erasure that softens Marcus’s intrinsic campness, and in my view softens the impact of a scene at the heart of The Home’s queerness.

I don’t suppose anyone’s going to lose sleep over this (though I appreciate it looks as if I have). Still, I think this edition will always be useless to queer theorists, literary and cultural historians, and students of Penelope Mortimer, except as a document to demonstrate what sensitivity readers were up to in 2023.

I also think it doesn’t serve the general reader: I’m one, who happens to be gay, and I want to read about what gay men were like in 1971; I want to feel the homophobia they experienced without editorial apology; I want their campness even if it’s troubling, even if it’s ‘offensive’, because I know that for gay people – Isherwood again – ‘High Camp always has an underlying seriousness’.

Last week, I wrote that people shouldn’t buy the 2023 reissue – and I’m uncomfortable about that this week as The Home is a terrific novel, and I can’t say the British Library’s tampering will materially affect the reading experience for most readers. Their edition is very handsome – and there are so many interesting titles in the series by forgotten women writers who deserve our attention.13

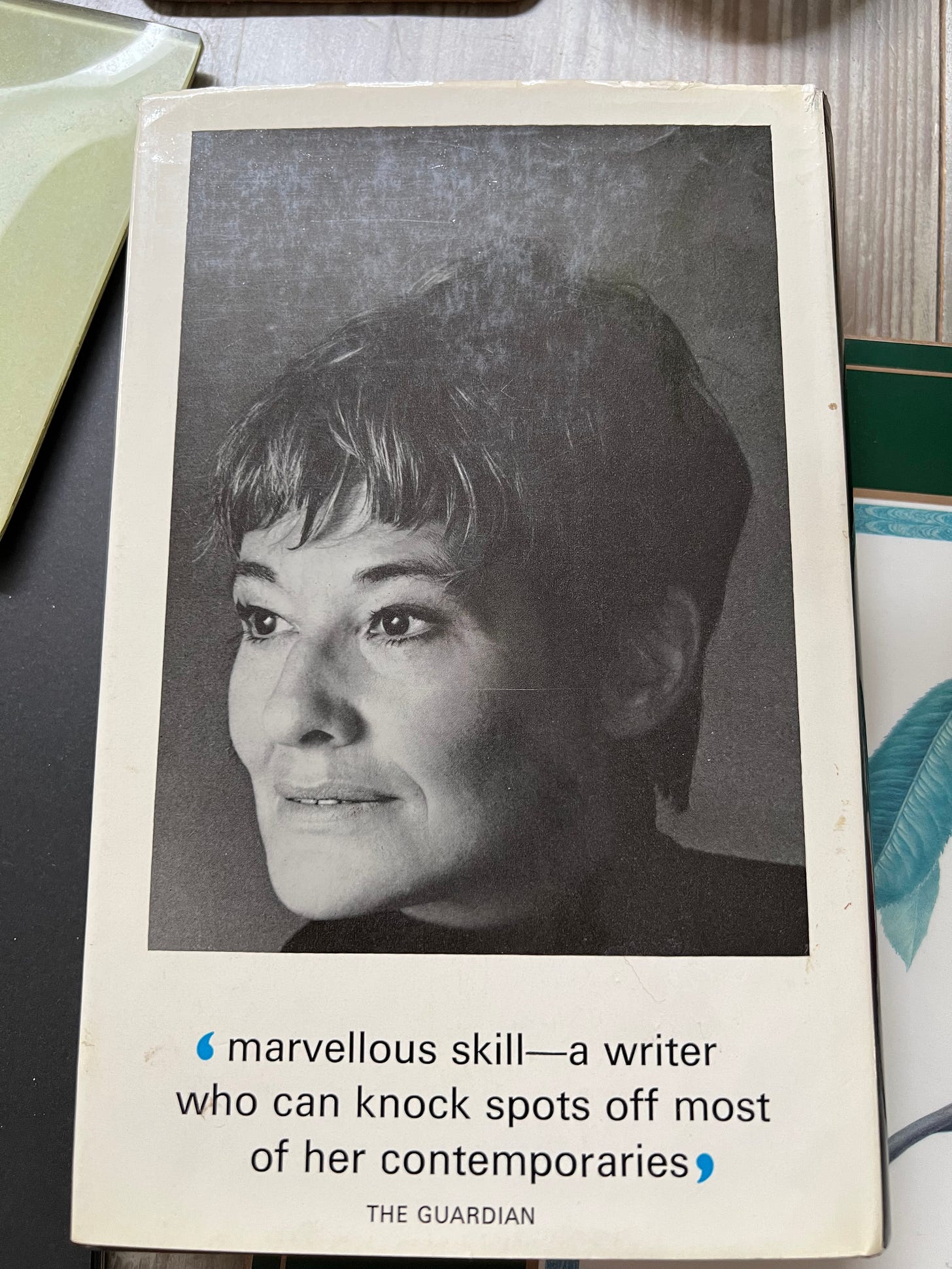

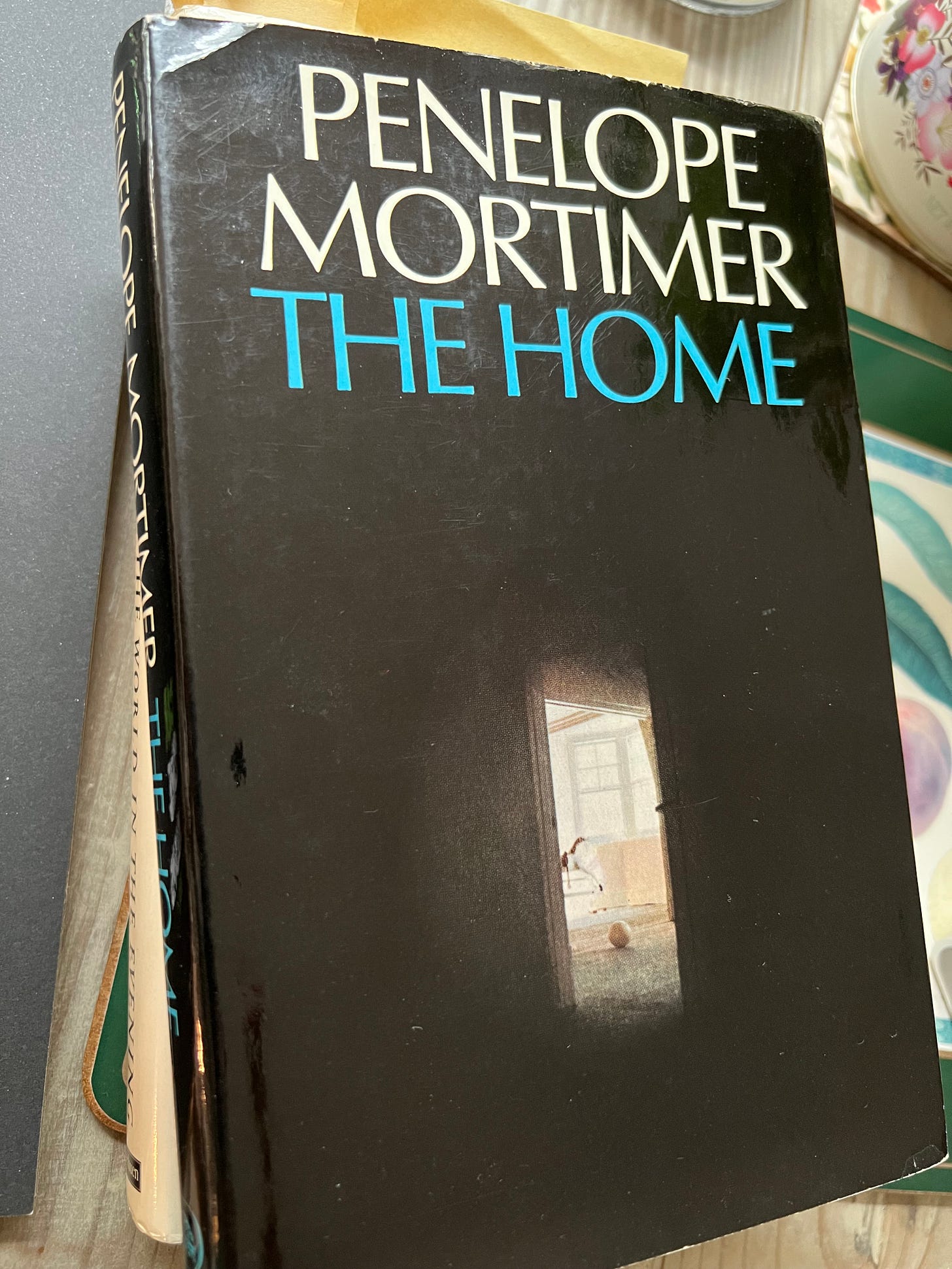

All the same, personally, I’m happy to have found a first edition for five quid at Little Stour Books in Canterbury (pictured above), and this is the one I’ll cherish, and will read again one day, because it’s the text Penelope Mortimer wrote, and the text she wrote is as queer AF.

If you think the edit I found was justified, please let me know. But surely if a publisher in 2023 bowdlerises an existing text, they should be clear, online, about what they’ve done. (I’ve written to British Library Publishing to ask what the other edits are; quaintly, they ask readers to contact them via Royal Mail.) And we have to talk about one inconvenient fact more than we do: sensitivity edits will always be shaped by sensitivity readers’ own human sensitivities, biases, knowledge gaps and fears of the other.

The writing exists, it exists, it exists. Be honest. The readers of a novel like The Home are likely to be able to handle it.

Thanks for subscribing.

https://www.thestage.co.uk/opinion/natasha-tripney-content-warnings-arent-patronising-they-are-a-crucial-access-tool [accessed 12 May 2023].

https://royalcourttheatre.com/whats-on/black-superhero/ [accessed 12 May 2023]. Danny styles the title of his play in caps.

http://www.steppenwolf.org/tickets--events/seasons-/2022-23/last-night-and-the-night-before/ [accessed 12 May 2023].

Penelope Mortimer, The Home (London: Hutchinson, 1971; repr. London: The British Library, 2023), French flap.

Daphne Merkin, Introduction to Mortimer, The Pumpkin Eater (London: Hutchinson, 1962; repr. London: Penguin, 2015), p. vii.

Mortimer, p. 78.

Lucy Evans, Preface to Mortimer, pp. ix-x (p. ix).

Mortimer, p. 5.

Mortimer, pp. 136-43.

Mortimer, p. 28.

Mortimer, The Home (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 163.

Christopher Isherwood, The World in the Evening (London: Methuen, 1954; repr. 1984), p. 125.

I messaged the series consultant Simon Thomas to tell him how much I liked The Home, his Afterword, and the series, and I had a lovely message back from him. He doesn’t work for British Library Publishing and is not responsible for editorial decisions concerning the texts. Dr Thomas writes the extraordinary blog Stuck in a Book and has done so, staggeringly, since 2007. In addition to his Afterword in the new edition of The Home, he writes about it beautifully here.

Interesting post, Samuel. I was just putting the finishing touches to my post for later today, and typing 'content warning...' on it, when your newsletter popped into my inbox...oh dear!

I think you raise some interesting and worthy points in here. I have written about sensitivity readers before, and I have mixed feelings: I think your points on allowing readers to access a text and appreciate the historical and cultural context of the time it was written, as well as reflect the reality of how some people did (and still do) think, can be a useful tool. To erase this can deflect from historical accuracy. As both a reader and a literary researcher/writer, these sorts of discoveries are invaluable of course. However, I have written before about such changes to outdated (but still popular) children's books, as I know from my Gen Z child that their generation find it much more unacceptable to find some of the content of these allowed to be re-published. I don't have a definitive answer! But I do have in my possession an original copy of The Home, which just arrived, and hope to start later today : )