I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

If you’re in London and can get to the Arcola and love good new plays, Sasha Hails’s Possession – not an adaptation of A.S. Byatt – is absolutely wonderful. It’s on for one more week.

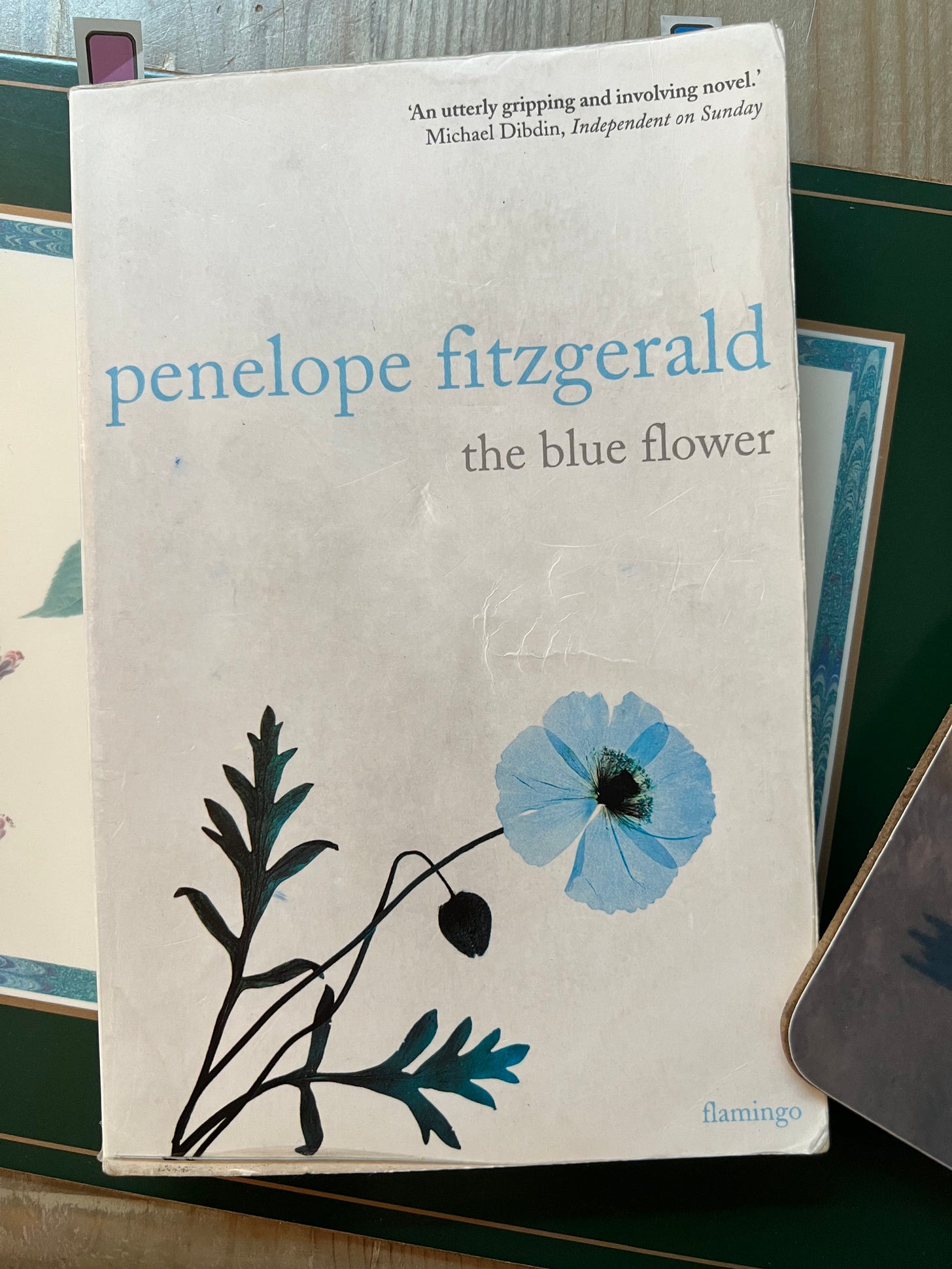

This week, I take a look at The Blue Flower and the exquisite subtlety of Penelope Fitzgerald’s art.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend,

Sam

In 1794, the twenty-two-year-old German Romantic poet Friedrich ‘Fritz’ von Hardenberg, later known as Novalis, fell in love with a twelve-year-old girl called Sophie von Kühn. In 1795, Fritz and Sophie were engaged; after Sophie’s death from tuberculosis in 1797, Novalis’s work – including his unfinished novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen – immortalised her.

These historical events are the basis for Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower, which is a portrait of the Romantic Fritz as a young man, and – interestingly, given that it’s an historical novel by a woman at the end of the twentieth century – of the girl Sophie as a Romantic object.

The novel charts the development of Fritz’s Romanticism throughout his childhood, education, apprenticeship, and courtship of Sophie. Novalis believed that ‘the world must become romanticized’; to romanticise, he said, was to ‘give a higher meaning to what is commonplace […] a semblance of infinity to what is finite’.1

At school, Fitzgerald’s Fritz insists ‘the body is not flesh, but the same stuff as the soul’.2

At university, he is taught by the idealist philosopher Fichte, who tells him, ‘Withdraw into your own mind!’,

We are all free to imagine what the world is like, and since we probably all imagine it differently, there is no reason at all to believe in the fixed reality of things.

After university, he is sent by his father to learn office management in Tennstedt, and here, he begins Heinrich von Ofterdingen.

At the heart of this tale is the elusive blue flower, which, in Fitzgerald’s biographer Hermione Lee’s words, ‘is the embodiment of that untranslatable German Romantic concept, “Sehnsucht”, an emotion of yearning which cannot be defined or fulfilled, but which is something like nostalgia or homesickness’.3 Several characters hear the opening to, and ponder the meaning of, Fritz’s story with its young man who longs ‘to see the blue flower. It lies incessantly at my heart, and I can imagine and think about nothing else’.

Fitzgerald was preoccupied with innocence, and as a genius who cannot ‘be judged by ordinary standards’ since he perceives ‘no real barrier between the unseen and the seen’, Fritz is a typical Fitzgeraldian innocent artist, at odds with the conventional world. He is lightly satirised, but never overtly ridiculed: many of The Blue Flower’s clever women find his ‘romantic tendencies’ fanciful, but Fitzgerald never doubts the seriousness of his Romantic project. In Tennstedt, he meets and falls in love with the perfectly commonplace Sophie, and immediately gives her a higher meaning. She becomes his ‘wisdom’, his ‘truth’, his ‘Philosophy’. When his brother Erasmus objects that he is ‘intoxicated’, Fritz answers, in poetry:

All humanity will be, in time, what Sophie

Is now for me: human perfection – moral grace –

Life’s highest meaning will then no longer

Be mistaken for drunken dreams.

As Fritz transfigures Sophie into his art, Sophie, amusingly, remains artless. In their first proper conversation, Fritz wonders loftily what she thinks of poetry; she replies, ‘I don’t think about it at all’. Shocked she does not believe in the afterlife, he protests, ‘Jesus Christ returned to earth!’; she answers, ‘I respect the Christus, but if I was to walk and talk again after I was dead, that would be ridiculous’. Erasmus is blunt: ‘Fritz, Sophie is stupid! […] Empty as a new jug’.

Sophie’s answers do, of course, hint at her effortless intelligence and spirit; and as the novel progresses, we grow to admire her, and feel for her because she is dying. The progression of her tuberculosis is charted by Fitzgerald with an almost appalling subtlety. Her surgeon undertakes three unsuccessful unanaesthetised operations on her tubercular tumour – and in the first, her body is violated in a public experiment attended by students. The horror of this is only implied: a landlady, waiting on the stairs for ‘screams’, hears nothing until ‘her patience was rewarded’.

Yet nothing, including Sophie’s sickness, is permitted to destabilise Fritz’s Romanticism: ‘I love Sophie more because she is ill’, he says. Throughout, he sees her as charming, immature, unfathomable, and – because Fitzgerald takes us to the landlady, away from the operating table – our view of her is never very far from his:

Sophie was pale, her mouth was pale rose. There was the gentlest possible gradation between the colour of the face and the slightly open, soft, fresh, full, pale mouth. It was as if nothing had reached, as yet, its proper colour or its full strength – always excepting her dark hair.

The thing about this objectification – which is what it would have been called in 1995, as in 2023 – is that Fitzgerald knows that it’s necessary to her novel. In her 2017 Reith Lectures, Hilary Mantel says:

For many years we have been concerned with decentering the grand narrative. We have become romantic about the rootless, the broken, those without a voice – and sceptical about great men, dismissive of heroes.4

But she warns of

a persistent difficulty for women writers, who want to write about women in the past, but can’t resist retrospectively empowering them. Which is false. If you are squeamish – if you are affronted by difference – then you should try some other trade.5

Fitzgerald is not false, and this is why The Blue Flower is a masterpiece. Although she finds a proto-feminism in other female characters, very little is known about Sophie von Kühn (she left behind an ungrammatical, ‘tersely written, naive, and childish diary’), and Fitzgerald resists ‘retrospectively empowering’ her – as a lesser, if feminist, novelist might.6 She insists on both an historical and a literary truth: because her novel is about a Romantic poet, qualities such as innocence, ineffability and elusiveness are necessary in a figure who is Romanticised by that poet.

Sophie can never quite be found, just like the blue flower.

As Sophie dies, her sister, an intelligent and complex woman, tends to her ‘open’ wound – a wound the poet Fritz tells himself he ‘must not see’. When he asks desultorily if he can nurse the girl he loves (there’s never any doubt about his love for her), the sister replies that he would be wanted not as a nurse but a ‘liar’, and that she does not know ‘to what extent a poet lies to himself’.

Sophie’s sister lives in a world where ‘flesh’ and ‘soul’ are distinct, in which she as a woman is required to face the ‘particulars’ of life – and of death.

Fritz lives not in that world, but ‘the kingdom of the mind’, where the body and soul are one. Still Romanticising Sophie as ‘my spirit’s guide’, he self-protectively and self-interestedly retreats into this poet’s world, never sees Sophie again, and goes on, as Novalis, to immortalise her.

Fitzgerald is a novelist of the first order because she observes this retreat in the historical/literary record, puts it into fiction, neither falsifies nor judges it, resists twentieth-century feminist agency for Sophie von Kühn – and allows us to make up our own minds about all of it.

It’s a wonderful book.

Novalis, trans. by and quoted in Peter Cochran, “Romanticism” – and Byron (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2009), p. xii.

Penelope Fitzgerald, The Blue Flower (London: Flamingo, 1995; repr. 2002), pp. 23-4. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 2, 8, 37-9, 53, 63, 78, 85, 103-6, 115, 119, 126, 138, 144, 160, 172, 240, 245, 273, 277-9.

Hermione Lee, Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life (London: Chatto & Windus, 2013; repr. London: Vintage, 2014), p. 396.

Hilary Mantel, Reith Lecture, I: ‘The Day Is for the Living’ (2017) <https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2017/reith_2017_hilary_mantel_lecture1.pdf> [accessed 8 July 2023] (para. 34).

Mantel, Reith Lecture, II: ‘The Iron Maiden’ (2017) <http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2017/reith_2017_hilary_mantel_lecture2.pdf> [accessed 8 July 2023] (para. 32).

Bruce Donehower, trans. and ed., The Birth of Novalis: Friedrich von Hardenberg’s Journal of 1797, with Selected Letters and Documents (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), p. 51.