I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

I began this week to write about E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View, the 1985 Merchant Ivory film adaptation, Julian Sands’s indelible George Emerson, and how Sands’s tragic death made me, a certain type of chronically uncool Generation X-er, rather nostalgic and sad.

Then I read Charlotte Higgins’s beautiful piece on the subject and realised it was pointless.

Suffice to say that I rewatched the film not that long ago, and it holds up. Sands’s two stolen kisses from Helena Bonham Carter’s Lucy Honeychurch – moments remarkably faithful to the same in the novel (and no apologies for the cliché, because stolen they are) – must be among the most romantic things ever seen on film.

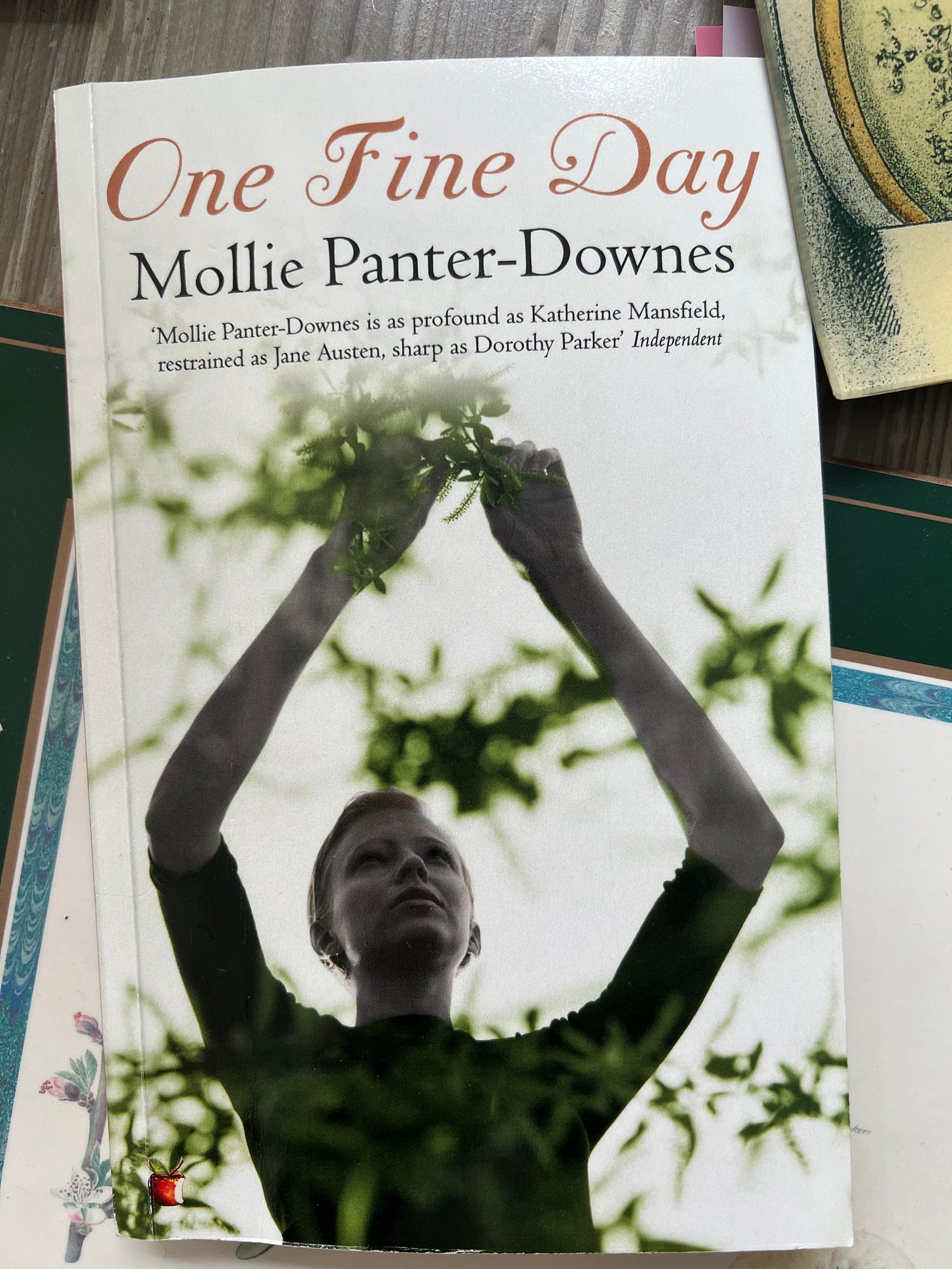

I’ll probably write about Forster’s novel one day; for now, some thoughts on Mollie Panter-Downes’s One Fine Day.

Enjoy the rest of the weekend.

Sam

Summer. England after a world war. A single day in the life of an upper-middle-class woman; her whole life in that day.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway? No, Mollie Panter-Downes’s One Fine Day – which owes a lot to Woolf’s 1925 novel, though its setting is not London but a village in the downs; the war that’s just passed is not the First but the Second; there’s no shell-shocked Septimus Smith figure throwing himself from a Bloomsbury window on to the rusty spikes of an iron railing; there are no flowers to buy – no evening party – for the Clarissa Dalloway figure, Laura Marshall.

But like Mrs Dalloway, One Fine Day is haunted by death, and almost every page alludes to the trauma of war: to men killed on the battlefields, German prisoners still labouring in the English fields, London women killed in the Blitz. And Laura undertakes journeys beyond her front door that recall Clarissa’s excursion for flowers, during which, like Clarissa, memory takes her into her past. There’s even a ‘what if?’ as there is for Clarissa: a man Laura might have married had she not met and chosen Stephen Marshall.

Nothing really happens. Panter-Downes is even less interested in plot than Woolf. But her opening chapter, in which her narrator tells us that the Marshalls’ ‘perfect village in aspic […] had very slightly curdled and changed colour’, makes clear the novel’s social concerns.1 Behind an exquisite portrait of the eternal English summer – behind a landscape that declares ‘I am England’ – are societal shifts: it’s a book about the destabilisation of old certainties for England’s middle class.

Laura and Stephen’s maids Ethel and Violet have gone: ‘How this frightful war has eaten up everything’, Laura’s mother says – by which she means, why haven’t the servants returned? Their garden is overgrown, ill-tended since the death of their gardener in Holland – and one of Laura’s tasks on this day is to find a new gardener, a task she fails. The local manor, in the hands of an aristocratic family for generations, has been sold to the National Trust. Stephen has returned from the war to resume his daily routine – the 8.47 to London, a bowler hat – but Laura’s grey hairs, their young daughter’s untidiness, and the ‘monstrous’ garden seem as distressing to him as any German bomb. Laura’s family ‘had helped to make the map an English pink all over the world’ – but the ‘comfortable nineteenth-century maxim, “Safe as Houses”’ no longer applies: ‘Nothing was safe’.

Nicola Beauman calls One Fine Day ‘deeply optimistic’, and Angela Huth writes that we leave the Marshalls thinking their marriage will survive, as having accustomed themselves to change, they are ‘armed with resolve to change’ themselves.2 At the end of her day, Laura is almost excessively thankful for her lot; at the end of his, Stephen is obliged to perform acts of domesticity, and comes to think it ‘preposterous how dependent he and his class had been on the anonymous caps and aprons who lived out of sight and worked the strings’.

A part of me wants to disagree with Beauman and Huth. This is a novel of slow-burning revolutions – but they’re not climactically seismic as they are in, say, Chekhov’s plays, and perhaps I longed for something louder and more meteoric for the somewhat unadventurous Laura, who doesn’t work but knows that her daughter will have to; who at 38 seems to a 2023 reader closer to 68; who is memorably looked upon by a handsome local man ‘as though she were a nice sofa’. ‘We conform, we conform, all of us’, she thinks at one point, ‘Why should anybody escape?’. The obvious subtext is why shouldn’t anybody, and twice she encounters an intriguing young hiker with a volume of Keats in his pocket, and his second appearance is deeply ambiguous – and I couldn’t help it, I made an escape out of it for Laura.

But I probably read more turns into her day than are there.

There is some stereotyping of the working classes – as Huth points out, Mrs Prout, a power-hungry charlady who speaks ‘Elizabethan’ like ‘a Shakespearian old nurse’, is not a successful character. But this gorgeous novel, which has an epigraph from As You Like It – the exiled Duke’s ‘True is it that we have seen better days’ – is what it is, like any work of art. And what it is, you come to realise, is a Song of All England: of its gentry, aristocrats, workers, travellers, loners, gypsies, eccentrics, vicars, refugees, poets; of its Phebes, Touchstones, exiled dukes, Audreys, Jaques, Rosalinds and not-quite Rosalinds; of its animals; and, of course, of its landscapes – near the end, a pony grazing in a field is described simply as ‘the eternal Stubbs in the eternal Constable’.

In Chapter VIII, there’s a passage about Bach:

girlishness could descend on Mrs. Vyner [the vicar’s wife] at the piano, playing a Bach chorale. Then her face became at peace, while her fingers arranged the pattern of exquisite logic, of utter reasonableness, fitting in piece after piece like drawers of a perfect little Chinese box, sliding them in quietly, returning to open one again and show the design, after all a little different, and then closing the doors on the completed thing, and sitting flushed, for a moment translated. Thus should life be, said Mrs. Vyner at her piano. Thus should it be, she would say, with the thorns of the Women’s Institute for the moment lifted from her brow, no chick or child clamouring round her feet, and her light grey eyes shining.

Like Mrs Dalloway, One Fine Day is not told entirely from one perspective, though it’s Laura who is the pivot (like Clarissa), and these are her thoughts. I found it impossible not to admire such a deep thinker: her insight into Bach’s craft, his music’s capacity to relieve us from our petty woes, is wonderful. I guess if you can’t find a way to join Laura on her uneventful journey, you won’t like this novel. I did, because I liked the modest, melancholic spirit of a middle-class, mid-century woman in the wake of the war, who sympathises with her compatriots’ losses, admires those among them with the ability to ‘Live lightly’, and, on a hill with a view, comes to count her blessings in her forever-changed corner of Arden:

For we are so lucky, so enormously lucky, thought Laura. Up here, in this clear rarefied light, their luck seemed immense. They were alive, they were all together […] here they were, the Marshalls, still a unit, still making sense in a world which every day seemed to signify less. Their wonderful, stupendous luck, thought Laura. Now that she had a free moment in which to stand back and look at it, it struck her as stupendous.

Thanks for reading. Do share my newsletter with anyone you think may be interested.

And speaking of sharing newsletters, I love Amy Abrahams’s writing about motherhood and other things:

And Kate Jones writes brilliantly every week about twentieth-century women’s literature:

Mollie Panter-Downes, One Fine Day (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1947; repr. London: Virago, 2013), p. 2. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 3, 5, 21, 47, 56, 72, 81, 89, 132, 138, 141-2, 165, 169.

Nicola Beauman, A Very Great Profession: The Woman’s Novel 1914-39 (London: Virago, 1983; repr. London: Persephone, 2017), p. 330; Angela Huth, Introduction to Panter-Downes (2013), p. xi.

Another great post. Thank you :) I used to love the Merchant Ivory films - particularly A Room With A View - Julian Sands, HBC and the adorable Denholm Elliott.

What a great post about One Fine Day – though the problem with your excellent Substack is that you're making my 'To be read' pile extremely high. Though please do write about A Room With A View one (fine) day too - I would love your take on it. I too was smitten with the film – it was very special to me and I will happily rewatch it – and those photos above are... well... yes, indeed, come on. And thank you for sharing my newsletter - I'm very honoured, especially from a writer such as yourself, I am not worthy. XX