No wonder the drama abounded in stories of the rise and fall of tyrants, of the suffocations of court life, of the jockeying of favourites. The dramatists had found it all in their own disgusting world […] this jostling, frightened, overcrowded world where all were vulnerable because all were expendable.1

Hello,

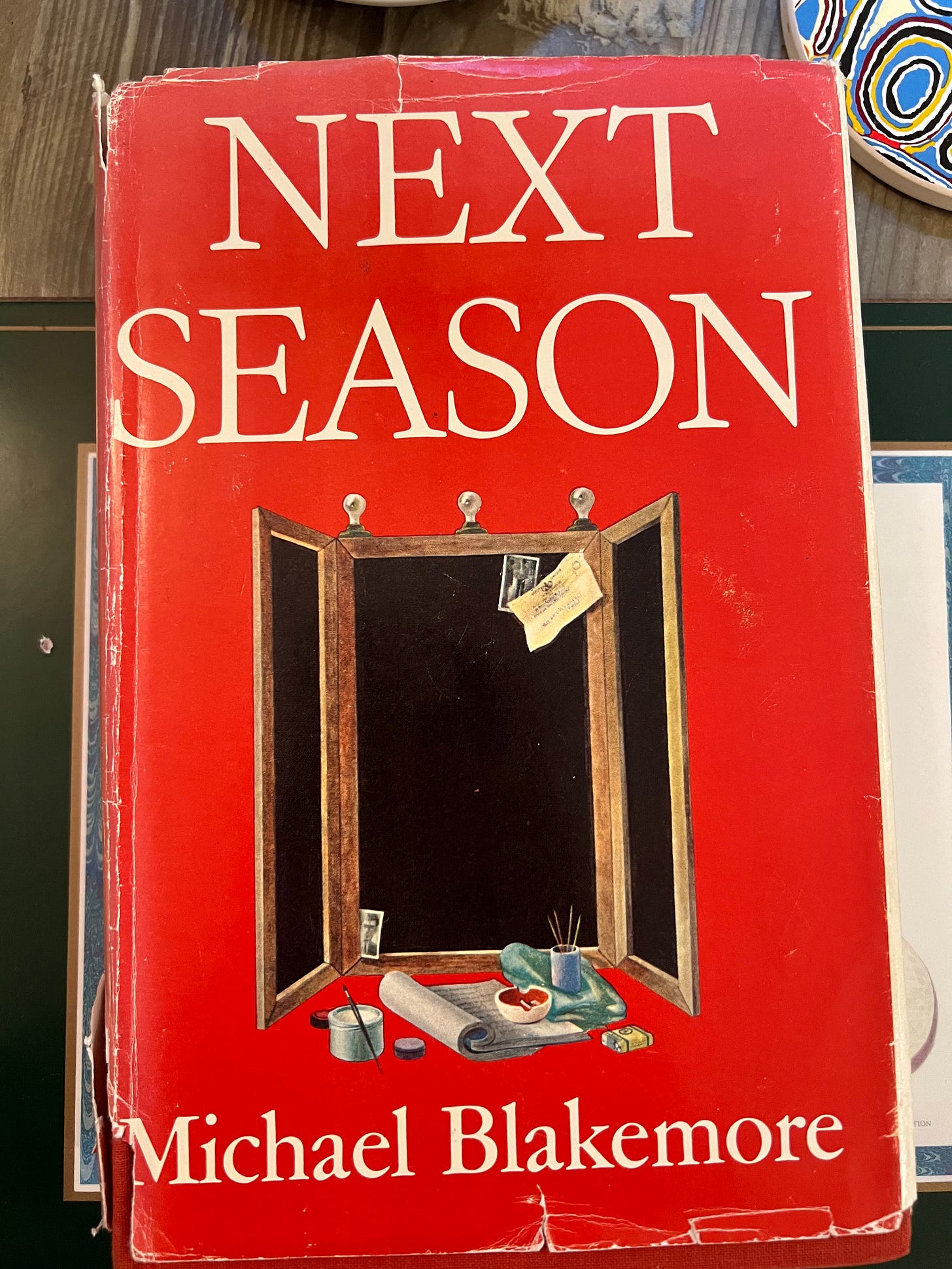

Last week, my new play opened. The build-up – casting, rehearsals, previews – was, needless to say, exhilarating/anxiety-ridden, and to fortify myself, I drank lots of wine returned to one of my favourite theatre novels, one of my favourite novels, Michael Blakemore’s Next Season – which I’d taken off my bookshelf for another look when Blakemore died at the age of 95 in December last year.

Blakemore was an Australian in the UK, a theatre director whose distinguished work included the premieres of Michael Frayn’s Noises Off and Copenhagen, Peter Nichols’s A Day in the Death of Joe Egg, and marvellous productions of the musicals City of Angels and Kiss Me, Kate.

He also made two films. The autobiographical documentary A Personal History of the Australian Surf (1981) reflects upon the dominance of sport in Blakemore’s Australian upbringing; and Country Life (1994) transplants Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya to Australia. I haven’t seen the latter since its release, but I remember admiring it: the conceit works because the tyranny of distance in Australia – the sheer space between rural outpost and metropolitan centre (Blakemore’s centre is the centre of Empire, London) – matches a similar tyranny in Chekhov’s Russia.

Blakemore was also a great memoirist, and I recommend his autobiography Arguments with England, as well as Stage Blood, an account of his time at Britain’s National Theatre in the early 1970s under artistic director Peter Hall, who is excoriated as an overstretched grandee interested in only one thing: the career of Peter Hall.

It is likely that Hall also appears in Blakemore’s only novel: he is probably the model for Tom Chester, a young, brilliant, fickle and controlling theatre director less interested in actors’ talent than their ‘determination’:

Talent’s important, of course. Of primary importance. But talent’s nothing without – well – ferocity. That’s what makes it interesting.2

Blakemore started his career in 1950s England as an actor, and Next Season is obviously a roman-à-clef: its protagonist, 29-year-old Sam Beresford, is an Australian in 1950s England making his way as an actor. He auditions for a repertory season at the fictional Braddington Playhouse in Yorkshire where the wunderkind Chester programmes The Duchess of Malfi, Macbeth and The Way of the World: Blakemore acted in rep in Birmingham, Coventry and Bristol – and also in Shakespeare’s Stratford, where he first met the wunderkind Hall.

Immediately, the reader is thrown into ‘the bait and the hook’ of this addictive world, into its bear garden of barbarity and near religiosity:

[Sam] made his way to the stage door past five young men, younger than him, probably fresh from drama school. They were pallid and solitary with nerves, one of them mouthing his lines like a prayer. They invited sadism, he reflected sadly; the profession does.3

Sam gets the job, and we follow him to Braddington, to his digs, to his rehearsals, to his love affairs, to his triumphant and less-than-triumphant opening nights, to his ultimate crisis of identity.

With the knowledge of the insider, Blakemore captures the energy, ambition, ego and single-mindedness required to make a career in the theatre; consequently Sam is a refreshingly flawed character – a vain, slightly arrogant, sexually frustrated young man on the make, though not so young that youth can forgive him all his sins.

Like Blakemore, he is a surfer. The subtitle to A Personal History of the Australian Surf is Being the Confessions of a Straight Poofter. ‘Poofter’ is a word that makes me bridle (unhappy memories of homophobic bullying in the Australia of the 1970s and early-1980s) and yet there’s something about the oxymoron – straight poofter – that makes me smile with recognition; it captures perfectly Australian men like Sam.

The ‘poofter’ in him is the artist, not just the eager young actor forever proving his sincerity to colleagues and rivals, but the true artist who knows in his heart that the arch-manipulator Hall/Chester is wrong: good acting must be about talent. The ‘straight’ in him is the sportsman who, no matter how far he has travelled, does not let go of the most clichéd aspects of his heterosexual Australian identity. There is a magnificent sequence prompted by a girlfriend who rings him to say that ‘there are waves, real waves! Breaking all along the beach,’ and he rushes down to catch these Pacific-like miracles in the brown Northern sea:

Some other swimmers had followed him into the water, and he saw with pleasure their impressed smiling faces; it was better than acting, a pastime to which there was absolutely no point save joy: nothing to win or lose. All you had to pay for was time.4

This is so lovely; it saves Sam from excessive pretentiousness, shows him to be a pretty well-rounded young man. Theatre is a matter of life and death for most of the characters – but so are other things for Sam. As the star of his own smell-of-the-greasepaint Bildungsroman he is, like many actors, vulnerable, self-absorbed, and not always likeable – but always complex, always human.

Only one stale comfort was available: all they were doing was putting on a play, and after all what could be less important?5

In the end, Sam fails as an actor because of a strain of envy that inhibits him from giving all of himself on stage. Next Season – next is the key word – is about something wretchedly true of theatre, and of life: our dreams and identities can become like a religion, even when they don’t quite fit us, and what the religion offers in the present is never enough. A theatre person gets a dream job, but the question never dies: what is next?

It is hinted that for Sam, as for Blakemore, the ‘next’ is not acting but a different kind of theatre-making. The hint underscores the ultimately winning message of the novel: we are all ‘striving to create the sort of world in which each of us operates best.’6

It is a shame Blakemore never wrote more fiction, but presumably the directing he discovered when he gave up acting was all-consuming. And one novel is better than none. Next Season is an intriguing document of dingy 1950s England; it shows theatre people at their worst and at their best; it is by turns funny, appalling, moving and honest.

Till next time …

PS If a film producer wants to make a film of this wonderful novel, I’m available to write the screenplay.

My play The Ballad of Hattie and James runs at Kiln Theatre, London, till 18 May:

The playtext of The Ballad of Hattie and James is published by Faber:

Michael Blakemore, Next Season (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), p. 356; the quote in the subtitle is from p. 151.

p. 348.

pp. 10, 26.

pp. 206, 209.

p. 126.

p. 349 (slightly paraphrased).

I read this novel years ago, thank you so much for reminding me of it!

So good on ambition, the constant internal hunger it creates.