Isabel Colegate’s The Shooting Party (1980)

Edwardian play-as-novel: the What, the Where, the When, the How, the Who, the Why

I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello, hello,

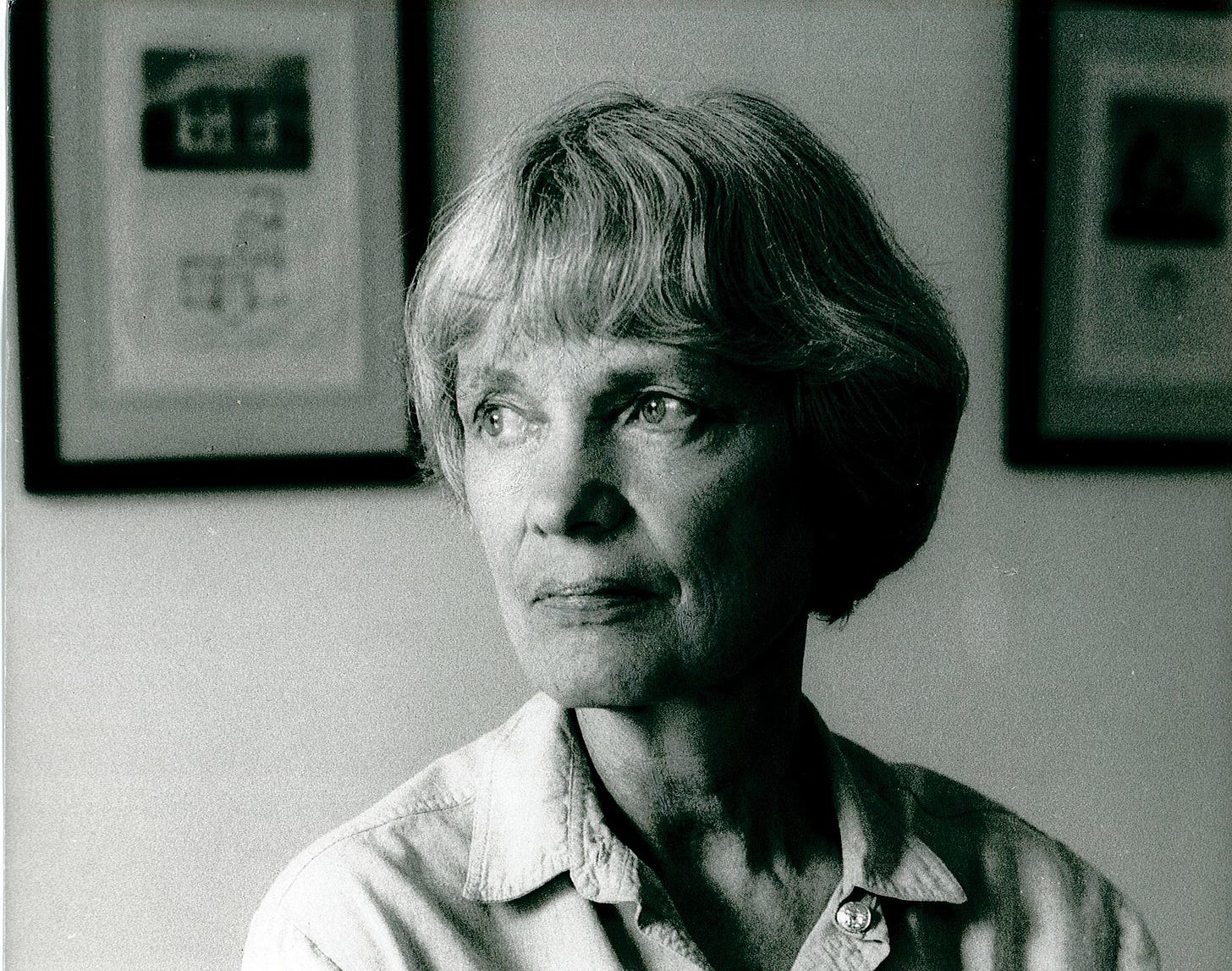

Isabel Colegate died in March at the age of 91, and this week I discuss her novel The Shooting Party. I didn’t think I’d like it, but I do; read on if you’re interested in why – some spoilers.

And whether you’re interested or not, watch Colin From Accounts, obviously.

Thanks for subscribing. Enjoy the rest of your weekend.

Sam

‘I should have thought that every English person’s deepest idea of England was of the country. Doesn’t England mean a village green, and smoke rising from cottage chimneys, and the rooks cawing in the elms, and the squire and the vicar and the schoolmaster and the jolly villagers and their rosy-cheeked children?’

‘It has not existed for many years now.’

‘It must exist. How could we all believe in it so if it didn’t exist?’

‘Exactly. We believe in it. That is why the idea is such a powerful one. It is a myth.’1

After I read about Isabel Colegate’s recent death, I found in my pile of unread novels The Shooting Party, read the back-cover blurb, thought immediately of Gosford Park and Downton Abbey, wondered if Julian Fellowes had been influenced by Colegate, discovered that he had, considered abandoning it on the prejudiced assumption that I’d be bored by a story about toffs shooting pheasants, got over my prejudice, turned to page one, found myself engaged, wondered why I’d never seen the 1984 film, and finished the book.

Then I went back to page one, not to reread the entire thing, but its opening passage – which the storyteller in me finds fascinating, because it gives away the story’s What, Where, When and How.

The What, we are told, is ‘an error of judgment which resulted in a death’ (the Who? – who died? – is withheld). This stems, evidently, from the weekend shooting party of the novel’s title at the Where, an Oxfordshire estate owned by ‘Sir Randolph Nettleby, Baronet, a country gentleman’. The When is ‘the autumn before the outbreak of what used to be known as the Great War’.

The How – the stylistic How, how the story will be told – takes up most of this fascinating opening. ‘You could see’, says the narrator, addressing us directly, the ‘mild scandal’ of the death ‘as a drama all played out in a room lit by gas lamps’. You could see it, that is, as an Edwardian play: framed by a proscenium, with people in costumes, people not that far removed from us, yet still historical, almost mythical,

discernibly people, but people from a long time ago, our parents and grandparents made to seem like beings from a much remoter past, Charlemagne and his knights or the seven sleepers half roused from their thousand year sleep.

This is beautiful stuff, and it is formally interesting because it declares the nature of the stuff to follow. You can complain if you don’t like what’s in The Shooting Party’s tin, but you can’t complain that you aren’t told at the outset what it is, or indeed, told that it’s actually in aspic, that it’s like an old play set in an aristocratic country house atmospherically lit by gaslight.

Colegate gives fair warning, then, that you’ll need a taste for Edwardian drama, for ‘mild scandals’ among toffs. And because these people are romanticised (roused like the Seven Sleepers), you’ll need a taste for a particular kind of Edwardian drama – probably one without the anti-Establishment radicalism of, say, a George Bernard Shaw; and probably one which romanticises the working class, since shooting parties operate on the sweat of beaters (who strike the ground to raise the toffs’ game birds) and loaders (who load the toffs’ guns). The Why of The Shooting Party is to catch a particular time, just after the King and the Kaiser shot at Sandringham together, just before their subjects started shooting each other. It’s a modest story, this opening says: the ‘mild scandal’ is ‘quite outshone’ (my italics) by the catastrophic war that begins after the story ends.

If this makes Colegate’s novel sound insufferably reactionary, in fact it is a social history about the passing of a particular kind of class-ridden England, and everything from its title down works as a metaphor for the destruction wreaked upon Edwardian certainties by the war, and by other forces.

But Colegate doesn’t explore social change witheringly. If you like your Socialist-Fabian-rationalist-‘friend [of] the famous playwright George Bernard Shaw’-Tolstoyan-placard-waving-suffragist-antivivisectionist-types to be true to their principles, you’ll be disappointed. Here, the radical described as all these things is also a mild-mannered schoolmaster straight out of the English myth in the quote above. When, protesting the shoot, he faces Sir Randolph, they (amusingly) find common ground over something at the heart of the myth that they both want to preserve. The radical is satirised, while Sir Randolph is shown in many shades, as entitled, fearful, flawed, likeable, compassionate, godless, patriotic, unsentimental, decent. This is a world in which everybody – everybody, even the radicals, even the poachers among the beaters – is in service or in thrall to Empire. In one troublesome passage, it’s suggested that the ‘cure’ to the brutal rituals of the Establishment can never come from the radicals, but only from within.

Colegate, the granddaughter of a baronet, presents this world in good faith, and doesn’t really deconstruct it – the very fact that her opening declares that it’s in aspic is its own deconstruction. I liked the subtlety of this, and thought there was just enough piquancy to the aspic to just about put the novel in the same league as the early twentieth-century play I thought of most often, Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard.2 I’ll conclude with three examples of this piquancy.

Firstly, the writing has that arresting blend of English pastoralism and bloody horror you find in the War Poets. The Oxfordshire ground is a place of ‘poetic light and stillness’, and when it is ‘thickly strewn with corpses’, you begin to see it as the fields of Flanders, the beaters as sacrificial Tommies, the shooters as pitiless officers.

Secondly, Colegate unsettles upper-class complacency with her subtle use of irony. One of the more interesting characters is a woman called Olivia, and we are told that once, she had said to her husband, about Society,

‘Supposing there are some other people somewhere, people we don’t know?’

He had looked at her seriously.

‘What sort of people?’

‘Perfectly charming people. Really delightful, intelligent, amusing, civilized. … And we don’t know them, and nobody we know knows them. And they don’t know us and they don’t know anybody we know.’

Bob had thought for a moment and then he had said, ‘It’s impossible. But if it were not impossible, then I don’t think I should want to know such people. I don’t think I should find anything in common with them.’

Isn’t this clever? It’s straight out of a Victorian or Edwardian play – a first-rate one. Olivia doesn’t really step outside of herself, and there’s no explicit narrative commentary, so the irony emerges through the dialogue’s gaps, and Colegate serves a welcomely salty morsel of Oscar Wilde or Shaw.

Finally, there’s a lovely portrayal of an idiosyncratic boy who has a friendship with a wild duck.3 He is Sir Randolph’s grandson, and intriguingly, it’s with him that the potential for change from within the system resides. Early on, Olivia’s snob of a husband says that ‘Art and life are two very separate things’. At the end, the boy becomes an emblem of a new age, and there’s the transgressive suggestion that it is the power of the art that follows war that wreaks the real societal change.

This is a consoling idea in our post-Covid lull, and I wanted to know more …

… but the curtain on the old play had fallen.

Till next Sunday’s book …

Isabel Colegate, The Shooting Party (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1980; repr. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984), pp. 100-1. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 1-2, 31, 37, 68, 81, 84, 101, 114, 157, 173, 175, 181.

Obviously, Colegate steals her title from Chekhov’s The Shooting Party, and she owes something to his stories. But she pokes fun at literary Russianness. Olivia finds English novelists lack ‘true perceptions about feeling’ compared with the ‘Real Thing’ – aka Turgenev. When she falls in love in a Russian manner, it discombobulates her. She is English, so a Russian kind of love cannot be her fate.

Perhaps an allusion to Ibsen’s The Wild Duck. But, as with Olivia and Russianness in the note above, the boy’s Englishness wittily scuppers anything too Norwegian.

Read the first three paragraphs of your post and stopped for fear of spoilers. And went to my shelves to get my unread copy... and am now cross because I’d misremembered. I have a collection of three short stories - A Glimpse of Simon’s Glory - and the novel Winter Journey. High time I read them, it seems...