Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont (1971)

And the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Hello,

This week I discuss Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor. Some spoilers (the idea that this could actually be an issue makes me smile).

If you’re in London: one week left to catch Ryan Calais Cameron’s Retrograde at Kiln, which I loved. It’s a clever unity of time/place/action play about Sidney Poitier, Paul Robeson, McCarthyism and Hollywood, with a superb performance by Ivanno Jeremiah as Poitier.

Enjoy the rest of the weekend.

Sam

Over the past ten years, I’ve read all of Elizabeth Taylor’s novels – no, not that one: as her biographer Nicola Beauman writes in The Other Elizabeth Taylor, the ‘fragility, delicacy, [and] allusiveness’ of Taylor’s writing meant that she wasn’t as well-known in her lifetime (1912-1975) as she should have been, and the fact that she shared a name with one of the most famous movie stars of the twentieth century ‘did not help a lot’.1

Taylor is still not that well-known. She’s always had champions, including Kingsley Amis, Philip Hensher, Anne Tyler, Hilary Mantel, Elizabeth Jane Howard – who writes in her Introduction to a Virago reissue of The Wedding Group (1968), ‘how deeply I envy any reader coming to her for the first time!’, and – I love the surprise of this – David Baddiel, who wrote the Introduction to a Virago reissue of The Sleeping Beauty (1953).2

But as Mantel writes in her Introduction to a Virago reissue, of Angel (1957), ‘Taylor was not the sort of writer who lives so as to excite prospective biographers’ (in fact Beauman did uncover a secret love affair, which distressed Taylor’s family), and a ‘clever, formal restraint is the hallmark of her fiction’.3 Restraint does not attract attention.

Given Taylor’s insecure reputation, I should really write about The Wedding Group or The Sleeping Beauty; her lesser-known novels, and her short stories, are probably more interesting than her most famous book, the Booker Prize-nominated Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont. But there are always other newsletters, and frankly Mrs Palfrey is my favourite.

In The Other Elizabeth Taylor, Beauman writes about the Booker judges’ first meeting for the 1971 prize, at which an ‘overbearing’ Saul Bellow declared of Mrs Palfrey: ‘I seem to hear the tinkle of teacups’.4 This ‘settled it’ – the other judges didn’t have the spirit to fight for a Forsterian tragicomedy about an old lady who lives in a residential hotel, and the Booker went to V.S. Naipaul for In a Free State.

When I started to summarise Mrs Palfrey’s plot as a way in to the writing of this newsletter, I was annoyed to find that I kept hearing the tinkle of teacups myself:

In the late 1960s, the ageing upper-middle-class Mrs Palfrey – cast aside by her family and newly resident at the Claremont Hotel in Kensington – establishes a friendship with the struggling young writer Ludo, who spends his days writing in the Banking Hall at Harrods, and pretends to be her grandson so that Mrs Palfrey is not shamed in front of her fellow residents.

Appalled by the deadliness of this, I flicked through the novel to remind myself why, a decade ago, I’d loved it. I landed on Taylor’s final paragraph, and was inspired to persevere. Then I simply gave way to the paragraph itself:

Their friendship grows, and in the grim basement room where Ludo lives, Mrs Palfrey comes to dinner to eat the steak and kidney pie she has bought for him from Harrods. But Mrs Palfrey and her fellow residents become copy for the callow youth’s novel They Weren’t Allowed to Die There (i.e. at the Claremont). Mrs Palfrey dies alone in hospital and

At the Claremont, they watched the Deaths column of the Daily Telegraph; but no notice of Mrs Palfrey’s death appeared. Elizabeth and Ian [her daughter and son-in-law] had decided that there was no one left who would be interested.5

I’d forgotten this poignant and brutal ending, and it suggests that although Naipaul deserved to win the 1971 Booker, Saul Bellow forgot the storms writers have found in teacups, forgot the profundity Auden saw in them: ‘the crack in the tea-cup opens / A lane to the land of the dead’.6

Perhaps I forgot the ending because there are so many things about Taylor’s beautiful story that are worth remembering – and so many memorable things in the rest of her work. A character in my play Wife thinks Taylor ‘somehow gets my life’, and many of her astute observations have always stayed with me, and spring to mind when life is at its most ridiculous or frustrating. Two quick examples from her 1949 novel A Wreath of Roses:

Early on, someone asks of Liz, regarding a painter, Frances, ‘What is she doing?’, to which Liz replies,

‘Playing the piano. Her painting is all going wrong. She is in troubled waters. So she plays the piano very loudly. Awful noises come out of it. A great confusion of sound. Dohnanyi. She has her vengeance on the piano. She gives it hell. She really is an absolute bitch to it.’7

This is great dialogue: the terse sentences, the amplification. I’m in troubled artistic waters almost every day, and when I try to get out of them by playing the piano as awfully as I do, that climax is often on my lips: being ‘an absolute bitch’ to the Yamaha is a catchphrase in our house.

Later, a man enters a hotel:

One yellow light shone beyond the hall door of the hotel. ‘Welcome’ said the door-mat, but to those going out.8

This sublime piece of topsy-turvydom is all you need to make sense of life: nothing makes any bloody sense; everything is always the wrong way round.

The one moment I’ve never forgotten in Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont concerns a certain John, Paul, George and Ringo. Although nobody could claim Taylor is a great chronicler of swinging London, she often wrote young characters, and her portrayals of long-haired Ludo and his girlfriend Rosie strike me as authentic. Their relationship is on and off, and,

In the middle of the day, he had gone for a walk, shrugging off stiffness. He passed and repassed the boutique where Rosie worked, he peered through the windows. It was teeming with the Sou-Ken flat girls, trying things on in their lunch-hour. Beatles beat forth. ‘Wednesday morning at five o’clock when day begins …’ Plaintive, beautiful. Shifting, coloured lights rayed the ceiling. He had entered, and hidden behind a rail of P.V.C. coats, his eyes on Rosie. (p. 65)

Ten years ago, I read this passage over and over. Why is it perfect, so touching?

The novel is about a widowed woman whose life is ending; whose daughter has forgotten her; whose grandson is ungrateful; who daily memorises a few lines of poetry ‘to train her mind against threatening forgetfulness’ (p. 108); who, having left Rottingdean for a new life at the shabby old Claremont in London, meets a likeable young writer who is impossibly polite to her and interested in her. Because of Ludo’s age – because it’s London circa 1967-70 – he’s connected to both the girls of the South Ken boutiques and to the Beatles’ ‘She’s Leaving Home’ in ways Mrs Palfrey could never be, and in ways that the writer Elizabeth Taylor (around 60 when she wrote the book) probably wasn’t.

So I feel the formal restraint that Mantel writes about is, here, the reticence of the old to dwell too long in the culture of the young for fear of betraying their outmodedness.

And then there’s the mistake in the lyric: of course it should be ‘Wednesday morning at five o’clock as the day begins’. Taylor is a meticulous writer, and I think this is also deliberate. The song is of course about a child leaving home; but the moving thing here is not just that the reference to the song supports the novel’s themes, but that the error in the lyric does: Mrs Palfrey’s youth is over, and her relationship with Ludo is as uncertain as the narrator’s grasp upon McCartney and Lennon’s famous words.

Then a two-word sentence makes the moment universal. The narrator – who is not Mrs Palfrey though closer to her than to any other character – finds the music ‘Plaintive, beautiful’. With its narrative restraint, its inaccuracy, and now its discernment, the passage becomes about Life and Mortality and Art and All Of It.

Anyone who’s heard ‘She’s Leaving Home’, irrespective of their age, knows that ‘plaintive, beautiful’ is precisely what the song is, knows that the Beatles created a timeless work of gorgeous art, knows – even if they muddle the lyrics – that it’s about a universal human experience.

It’s a plaintive and beautiful moment in a plaintive and beautiful novel.

And there’s your earworm for the day.

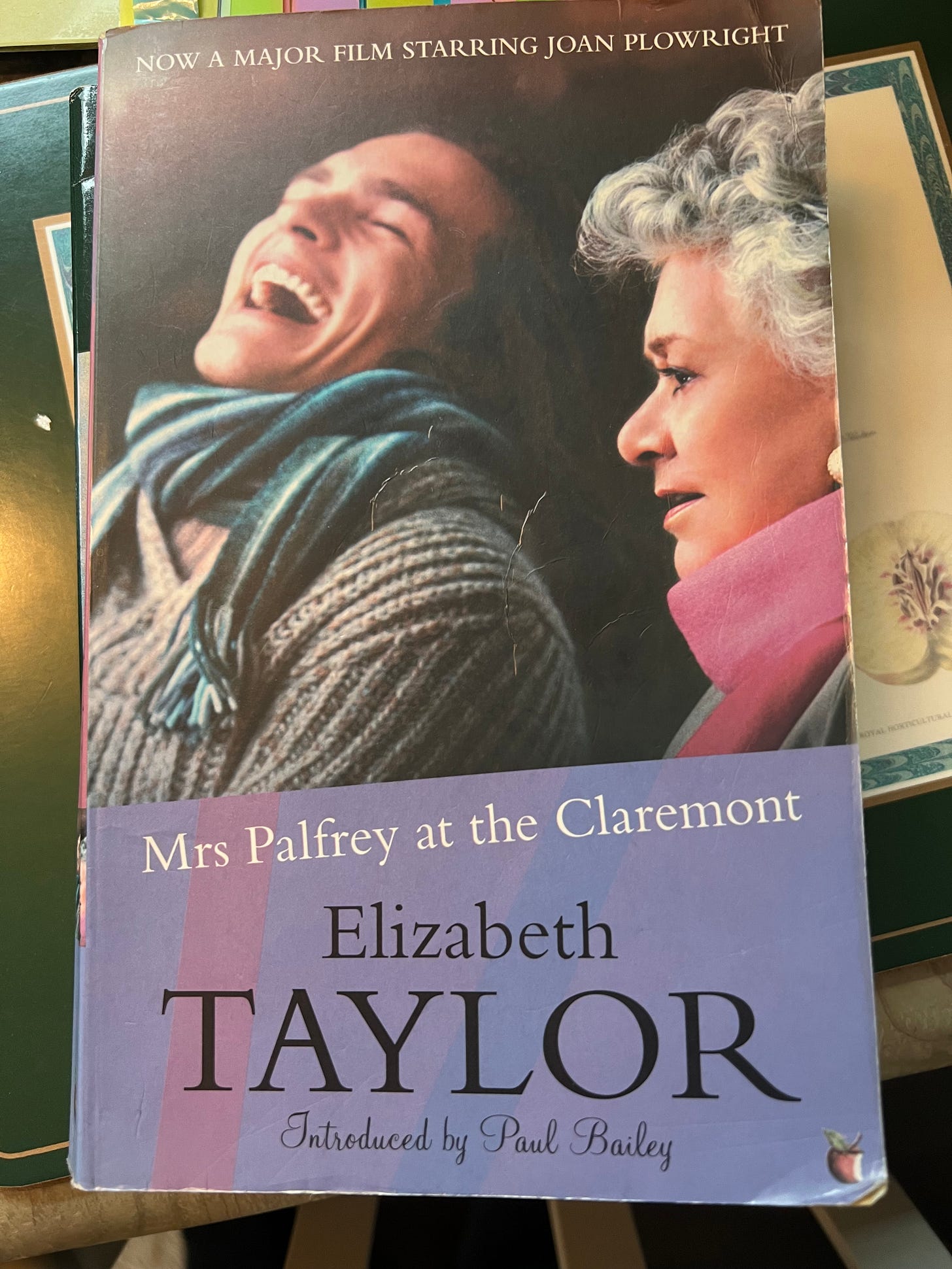

One last thing: avoid the 2005 film starring Joan Plowright (doing her best). It’s a long time since I’ve seen it, but from memory it Hollywoodizes London, and witlessly brings the story into the 2000s. I think it contains a joke about Terence Rattigan, but the Claremont becomes a Sofitel-type hotel with a dining room that captures none of the run-down gentility of the novel’s dining room, where, like a scene from Rattigan’s Separate Tables, the old residents – Mr Osmond, Mrs Burton, Mrs Post, Mrs Arbuthnot – gripe over their ‘cold and wrinkled food’ (p. 197), their fricassee, their sherry trifle that’s ‘sopping wet, but not with sherry’ (p. 176).

London residential hotels such as Mrs Palfrey’s had vanished long before 2005; likewise, aspiring novelists have been unable for decades to take their ‘writing and a few sandwiches’ (p. 28) to Harrods Banking Hall. Detached from Taylor’s 1960s London, the screenplay’s story becomes as banal as my summary of the novel’s, especially when it schmaltzifies (that’s absolutely a verb) Mrs Palfrey and Ludo’s relationship by overstating its grandmother-grandson aspects. For Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey, the friendship is more complex – but the film is afraid of this, and deals with the subtle non-platonic aspects to the love story with a crass reference to Harold and Maude. It gets everything wrong.

Happily, the iconic Australian playwright Ray Lawler got it right in a 1973 Play for Today adaptation. As the Lonely Heart Mrs Palfrey, Celia Johnson lets her yearning for connection tremble behind the veil of her ‘lovely manners’ (p. 205). And Joseph Blatchley is wonderful as the well brought up Ludo, on his uppers in London’s bedsitland – I love that in the novel he warms the pie from Harrods ‘on an asbestos mat above the gas-fire’ (p. 95).

This Play for Today is a window into a lost world, and years ago, I managed to find a bootleg – I know, my delinquency knows no bounds. Thanks to Alex Ramon for letting me know that it’s now on YouTube.

Till next time. And thanks for subscribing – I appreciate it.

Nicola Beauman, The Other Elizabeth Taylor (London: Persephone, 2009), pp. 395, 398.

Elizabeth Jane Howard, Introduction to Elizabeth Taylor, The Wedding Group (London: Chatto & Windus, 1968; repr. Harmondsworth: Penguin/Virago, 1985), p. x.

Hilary Mantel, Introduction to Taylor, Angel (London: Peter Davies, 1957; repr. London: Virago, 2013), p. 2; Beauman, passim (particularly pp. 74-85), 401.

Beauman, p. 369.

Taylor, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont (London: Chatto & Windus, 1971; repr. London: Virago, 2006), p. 206. Other page numbers in this newsletter refer to this edition.

W.H. Auden, ‘As I walked out one Evening’, in Collected Shorter Poems, 1927-1957 (London: Faber, 1977), pp. 85-6, ll. 43-4.

Taylor, A Wreath of Roses (London: Peter Davies, 1949; repr. London: Virago, 1994), p. 12.

Taylor, Wreath, p. 146.

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this, having only come to the magnificent Mrs P earlier this year and with the rest of Taylor’s work yet to discover. I’m over the moon that my teen idol, David Baddiel, is an appreciator of her writing! I couldn’t get hold of the recent adaptation after I’d read the book, but it sounds like that’s not such a bad thing. I did enjoy the Play for Today on YouTube.

You’re right, of course: Angel is atypical and extraordinary. Fascinatingly disconcerting to read and feel sympathy for such a solipsistic character - hard to think of another writer who achieves that with so little authorial comment to guide the reader.

I did see the film, not least because Una Stubbs was in it - all too briefly. I remember little about it other than the fact that it didn’t really work. How could it? It’s another case of the adaptation dilemma: how to convey more than the events of the narrative.