Hello,

The Long View (1956), Elizabeth Jane Howard’s portrait of Antonia Fleming, an upper-middle-class Englishwoman unhappy in her life and marriage, remains one of the best books I’ve read since I started this Substack; in a newsletter in April, I marvelled at Howard’s ability to refresh conventional five-act storytelling structure (the story moves backwards in time and the characters become more complex as they get younger). It’s a novel that all writers should read:

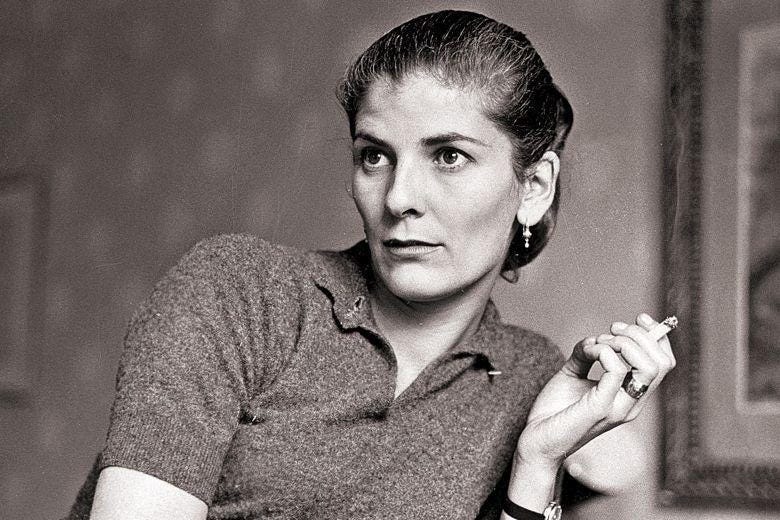

Elizabeth Jane Howard’s The Long View (1956)

I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

This week I took Hilary Mantel’s advice in her Introduction to the Picador Classic edition of The Long View, and read another of Howard’s ‘little miracles,’ After Julius (1965).1

Like The Long View, this superb novel takes something conventional – here, the motif of a weekend in the country – and makes it feel new-minted. It is about the relationships between five damaged and vulnerable people: upper-middle-class Esme, her publisher daughter Emma, her pianist daughter Cressy, her ex-lover Felix, and Emma’s new friend Dan, a working-class poet. The ghost at the feast at the Sussex home where they gather for the weekend is Esme’s husband and Cressy and Emma’s father, the Julius of the title. Twenty years before the novel’s events, at the time of Esme and Felix’s affair, Julius sailed to Dunkirk to help with the evacuation and was killed by the Luftwaffe – a deed not entirely comprehensible to the people left behind. The footprint he has made on the paths of their lives is enormous.

As she does in The Long View, Howard plays with time and perspective elegantly, and employs sophisticated irony to dramatize how ignorance of the details of the lives of others is both a bother and a blessing. She uses a third-person narrator, but most chapters convey, in essence, the singular perspective of one of the five main characters. Chapter One is titled ‘Emma,’ Chapter Two ‘Esme,’ Chapter Three ‘Dan,’ and so forth – gradually, we see the long view, see how the characters’ paths intersect, see the detail of Julius’s footprint in ways those who come after him cannot. In a ‘Felix’ chapter, Esme gives Felix a file containing documents about Julius: Julius’s brother Mervyn’s account of the Dunkirk expedition; interviews with the signalman Julius saved; clues as to Julius’s motivations (did he go because of his discovery of Esme and Felix’s affair?). The file is obviously an artefact of significance – Felix understands ‘that the document made [Esme] feel very emotional, even now.’2 But in the next ‘Cressy’ chapter, the file reappears and loses its significance:

Cressy dried, realized that she hadn’t brought her dressing-gown, and wrapped in the bath towel she wandered to her room. On the way she came face to face with Felix who dropped some sort of file he was carrying and said ‘Christ!’

It is merely ‘some sort of file’ in Cressy’s chapter because Cressy does not (cannot, in storytelling terms) see just how impactful its contents have been on her life.

Howard is an adept at this technique of internalized focalization within a narrative that is ostensibly omniscient or non-focalized; it allows her to cunningly withhold or reveal information. We are alive to the significance of the file in the way that Felix is but that Cressy is not – and in fact in the next chapter we will come to know every word inside it. Yet we can never assume our view is complete: later we realize just how little we knew about Cressy when a turn in the path takes her story into a wonderfully emotional clearing.

This is in part a tale of tangled love, and there’s a melancholy air to it that feels a touch Shakespearean. I also thought of Stephen Sondheim’s ‘Send in the Clowns’ from his and Hugh Wheeler’s A Little Night Music (1973), and the Ingmar Bergman film that inspired that musical, Smiles of a Summer Night (1955).

In Bergman’s film, Desirée says to her mother as the mother completes her morning game of solitaire, ‘If you cheat a little, it always comes out.’ The mother replies, ‘You are wrong there. Solitaire is the only thing in life which demands absolute honesty.’3 To which we might reply, ‘Solitaire and writing’: characters can cheat, but writers cannot cheat their characters.

Howard is a writer who is absolutely honest, so when the game of life does not come out in After Julius, it is very sad: it seems to me an important social document about both the trauma of the Second World War; and, with several unvarnished passages about sex and rape and abortion, about early-1960s women – about their bodies, their compromises and suffering when it came to sexually entitled men.

Howard is a writer who is absolutely honest, so when the game of life does come out, as it essentially does for Cressy and Emma, it’s convincingly lovely. Emma and Dan’s relationship is flecked with danger and misunderstanding (and an episode of upsetting violence), but it’s one of the most intriguing depictions of young love I’ve ever read (Howard explores rigorously the class tensions between them, and had the book been filmed in the 1960s, the boatman’s son Dan would have been played by Albert Finney or Tom Courtenay or Alan Bates, and the publisher’s daughter Emma by Julie Christie).4

Howard is a writer who is absolutely honest, so when along with Esme we read the contents of the Julius file, we read pages and pages of bad writing: Julius’s brother Mervyn makes ‘one feel, with every sentence, that writing must be very difficult.’ Esme has the file because of Mervyn, and so Howard must have Mervyn, not her elegant narrator, tell the bare facts of Dunkirk. Many novelists would shy away from such fastidiousness; they’d package events in exquisite non-focalized omniscient prose; they’d cheat. Howard doesn’t, and it’s moving.

Howard is a writer who is absolutely honest, so we are told this about the perennial pain of life when the game does not come out:

In all these years while [Esme] had been growing old, she had not learned what to outgrow. When she suffered pain, fear, or any misery, her age became meaningless; she was a child, a young woman, in the wrong body: her throat ached as it had always done before tears; her reason vanished and the same, crying question recurred; tears scalded, sobs racked, injustice rankled, pity was too close for comfort: she could have been six, or sixteen: not, surely, nearly sixty. But the side-tearing, inescapable joke was that she was nearly sixty. Too old for what she wanted from her life. She suddenly remembered Julius, that last morning – crying because he was too old to fight, and the conscious cruelty with which she had said: ‘There’s nothing you can do.’ So he had gone quietly off to do something he thought he could do and died in the process. She knew a bit what he felt like, now, she thought.

What more is there to say? Read Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Till the next novel …

Hilary Mantel, Introduction to Elizabeth Jane Howard, The Long View (London: Jonathan Cape, 1956; repr. London: Picador, 2016), p. xvi.

Howard, After Julius (London: Jonathan Cape, 1965; repr. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976), p. 160. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 164, 202, 235.

Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman, trans. by Lars Malmstrom and David Kushner (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960), p. 74.

There was a television series made in 1979; Paul Copley played Dan and Petra Markham played Emma.

Thank you for this wonderfully illuminating review. I have read the Cazalets so recognized the technique you describe w the file that she does to such great impact in those

human, honest novels.

Covid killed my appetite for fiction. I found it near impossible to read and during that time, tried and failed with this very book. My failure is no reflection on Elizabeth Jane Howard whose work I adore. Must make a second attempt.