Hello,

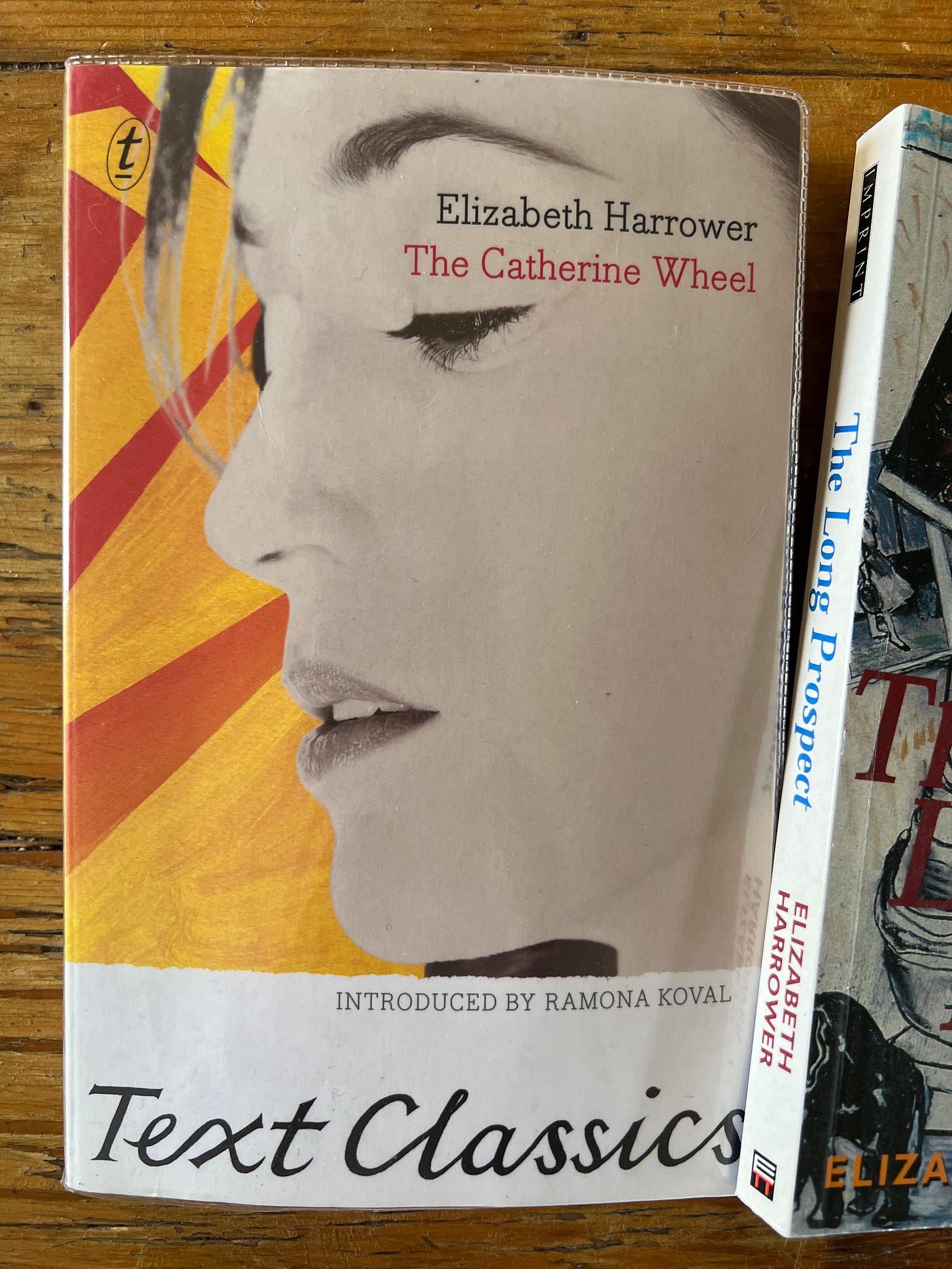

The Sydneysider Elizabeth Harrower (1928-2020) moved to London in her 20s at the beginning of the 1950s, and the narrator of her third novel The Catherine Wheel, published after she had returned home at the end of the decade, is a twenty-five-year-old Australian in London.

Clemency James is a clever, practical, well brought up, relatively well-off and well-connected law student and teacher of French who – even if she knows that occasionally her Oxford-educated friends view her as ‘the Wild Colonial girl’ – fits easily enough into English society.1

Yet the London you live in is rarely the London of your dreams, the London you’ve read about in books; and Clemency’s London is pretty grim, a place to which it feels she does not belong and from which she should escape. In the opening paragraph, the ‘wind from Siberia’ comes ‘down Bayswater Road from the direction of Marble Arch somewhere in a straight line beyond which, half a world away, Siberia was taken to be’, and it prompts in Clemency this wry reflection:

Gently, somehow sympathetically, with a secret sort of throb, my ears ached against it, but rather more drearily and with a sense of injustice my eyes watered as I narrowed them at the steely dark sky and swirling smoke. The centre of the universe! The brilliance of the winter season!

To many of Clemency/Harrower’s compatriots who have made a similar journey, that ‘injustice’, and those exclamation marks – ironic, sarcastic – are relatable. Australians are consumed by wanderlust, but many have suffered a bitter London winter and wondered: Why? What the fuck am I doing here? The novel proceeds brilliantly to depict a bedsit-land that many natural-born Londoners don’t know about: a world of hovering, deceptively solicitous landladies, with their casual racism and rapaciousness; of gas-fires with hungry meters; of dingy restaurants; of baths in ‘hard London water’ (never showers: on this exasperating matter Clemency cries to a bath-snob English friend, ‘You are all under-privileged’). The story gets darker as the days get brighter, and when the daffodils arrive, Clemency finds it almost impossible to believe that England is capable of such a thing as spring: the sun hangs ‘surprisingly’ in the sky.

This unsettling metropolis is the location for an unsettling story about a friendship that becomes an obsessive love. Clemency meets in her building a thirty-year-old ‘improbable untrustworthy character’ named Christian, a failed actor employed by her landlady as a window cleaner. Christian is in a relationship with an older woman named Olive, who was once his landlady: they are an odd but plausible couple, separated by class but connected by their experiences of family trauma.

Gradually, we learn of the violence and loss in Christian’s childhood and how it has formed his personality – ‘personality’ is a significant word, used by Clemency in relation to Christian several times. An ‘infantile adult’, a ‘menace’, an ‘aged Teddy boy’, an alcoholic with a string of unpaid debts, he is utterly captivating: it’s impossible to look away from him, just as it’s impossible to avert one’s eyes from a blazing Catherine wheel. Christian’s friend Rollo, as damaged by his own family and by booze as Christian, says to Clemency that Christian is ‘lacking a miracle’:

And the miracle – I don’t know if you’ll understand quite – would be to start again from the beginning. It is ridiculous, isn’t it, for a man of my age – or even his – to need a happy childhood?

Clemency does understand – and can’t help but feel fondness towards the unhappy Christian, with his ‘penetrating capacity to know himself’. After he engages her to teach him French in preparation for some fantasy job in the Paris of his dreams, she is helplessly ‘clamped’ to him. The novel follows the psychodrama of their relationship.

In Harrower’s The Watch Tower (1966), the compelling Felix Shaw is a chauvinist monster who, utilising all the gaslighting techniques available to him as a mid-twentieth-century Bluebeard, psychologically abuses two sisters inside the prison of his beautiful Sydney home. The watch tower of the title is metaphorical – one sister, who dreams of Russia and of ‘beauty and terror and so much more than we know’ shows the reader a path towards freedom.2 In some ways, The Catherine Wheel’s Christian seems a precursor to Felix, but here things are more even-handed: Clemency’s is a different kind of imprisonment from the one that The Watch Tower’s sisters suffer. For much of the novel we are in Clemency’s head as she tries to comprehend the broken (bipolar?) man who needs her help, and we are on her side when she vilifies her more stable friends for their advice to leave him.

Two obvious things about Catherine wheels: they burn themselves out, and, unlike other kinds of fireworks, they are fixed in one place. Christian is dynamic, ablaze – yet simultaneously immobile, stuck. Clemency, the Australian outsider, not fixed to bedsit-land, gets too close as he spins and burns, yet with his demise inevitable, I half expected her to see the path to freedom through the daffodils – the path away from the supposed ‘centre of the universe’, the path Harrower herself took back to her Sydney home.

But Harrower isn’t one for convenient endings or false resolutions. In a conversation with the journalist Ramona Koval, who wrote the Introduction to the edition published by the estimable Text Publishing, she said that ‘somehow or other [I] feel that I know something interesting about human nature that I have a deep wish to tell everybody’.3 What she knows and tells us is sometimes appalling, but I recommend her novels for their psychological acuity and emotional candour. The Catherine Wheel explores, unrelentingly, the ‘exertion of the soul’ required by love – and I found it devastating.

Till the next novel …

Elizabeth Harrower, The Catherine Wheel (London: Cassell, 1960; repr. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2014), p. 207. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 1, 38, 56, 62, 129, 130, 181, 184, 196, 225, 324. The subtitle quotation is from p. 323.

Harrower, The Watch Tower (Sydney: Macmillan, 1966; repr. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2012), p. 148.

Harrower, quoted in Ramona Koval, Introduction to The Catherine Wheel (2014), p. xii.

I've never heard of Elizabeth or her novel, but if I came across it now I would definitely pick it up. Thank you!

The cover on that edition! Love it.