I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

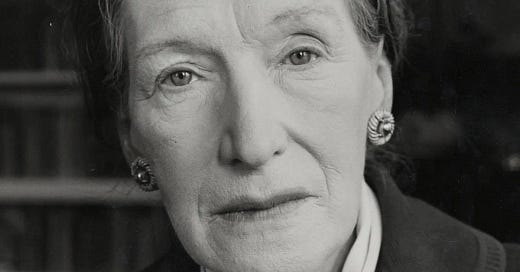

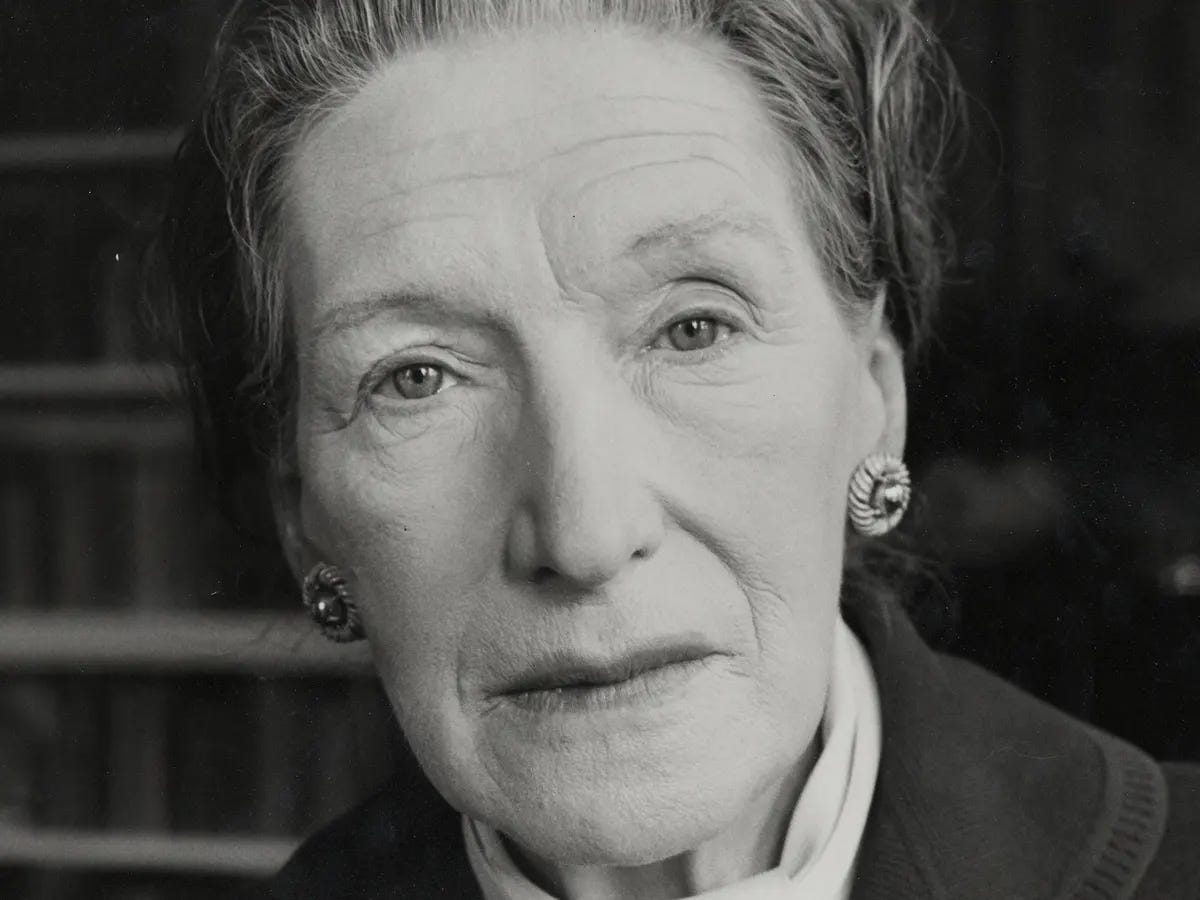

This week, I look at Elizabeth Bowen’s The Heat of the Day.

If you’re in London, enjoy the heat of this day; wherever you are, enjoy the rest of your weekend.

Thanks for subscribing.

Sam

The novels of the Irish-British writer Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973) are surely like Henry James’s, and can surely be called modernist, in that their riches lie in the seams beneath their surfaces:

There can occur in lives a subsidence of the under soil – so that, without the surface having been visibly broken, gradients alter, uprights cant a little out of the straight.1

There are often shades of the Gothic in them – the dead walk among the living, the past bears down on the present:

What’s unfinished haunts one; what’s unhealed haunts one.

Plots are less important than human psychology: characters are slightly dislocated from their worlds, each other and themselves, and their feelings are as narratively significant as their actions:

She had had the sensation of being on furlough from her own life.

Time feels disordered, because:

One cannot time feeling.

Bowen is not Virginia Woolf or James Joyce; nevertheless, the experience of reading her is akin to piecing together a jigsaw puzzle of some impressionist painting – and when you finish, things appear, well, unfinished.

I’ve read a few Bowens over the years, including during lockdown her exquisite A World of Love (1955), but only this week got to one of her most famous books, from which all the quotes above are drawn, The Heat of the Day.

I loved everything Jamesian and modernist about it; it’s a riveting study in ambiguity.

If you haven’t read it, it’s not giving away too much to say that it concerns a love triangle between a woman and two men in London in 1942 (Bowen had personal experience of love triangles). Stella, who works for the wartime government, loves a spy at the War Office, Robert, who was wounded at Dunkirk. They are pursued by a counterspy, Harrison, who tells Stella that Robert is a traitor: ‘the gist of the stuff he handles is getting through to the enemy’.

As the ramifications of this disclosure play out – and it’s a disclosure made in Harrison’s own interests more than the country’s, so that he, too, can be read as a traitor – you’re never quite sure what Stella, Robert and Harrison know or don’t know.

This is a novel of the unspoken in a world where, conceivably, to speak is to betray. As the wartime Ministry of Information propagandised, Careless Talk Costs Lives!, and, living as she does ‘at the edge of a clique of war’, the clever and independent Stella ‘command[s] a sort of language in which nothing need be ever exactly said’.

And yet, like most of the characters in the novel, Stella talks a lot; Bowen’s dialogue and narration are anything but laconic. Stella, Robert and Harrison examine their fraught lives in long, poetic, self-reflective orations, and this narrative passage about a London harrowingly yet somehow ravishingly at odds with itself is typical:

[Stella and Robert] had met one another, at first not very often, throughout that heady autumn of the first London air raids. Never had any season been more felt; one bought the poetic sense of it with the sense of death. Out of mists of morning charred by the smoke from ruins each day rose to a height of unmisty glitter; between the last of sunset and first note of the siren the darkening glassy tenseness of evening was drawn fine. From the moment of waking you tasted the sweet autumn not less because of an acridity on the tongue and nostrils; and as the singed dust settled and smoke diluted you felt more and more called upon to observe the daytime as a pure and curious holiday from fear. All through London, the ropings-off of dangerous tracts of street made islands of exalted if stricken silence, and people crowded against ropes to admire the sunny emptiness on the other side.

Of course writing so simultaneously stirring and horrific, alive to the incongruous, and authentic, could never feel tedious.2 And the novel is about spies during war, so however lengthy its prose, it always operates as a page-turning thriller. I haven’t seen the 1989 Harold Pinter-scripted TV film, but as I read, the noirish atmosphere made me think of films like Double Indemnity and Casablanca, and wish that 1940s Hollywood had pounced upon the novel the moment it was published.

Perhaps it was too noirish for Hollywood, too morally ambivalent. Ultimately, Casablanca is a simple love story, and for all Bogart/Rick’s neutrality, we’re never really in doubt about whose side he’s on. The Heat of the Day is not only a love story, but a great psychodrama about love, and it asks troubling questions about the neutrality of the human heart in a world of political partiality.

When Harrison tells Stella about Robert’s Nazi connections, he calls Robert an ‘actor’, and says that ‘if a chap were able to act in love, he’d be enough of an actor to get away with anything’. This attempt to minimise Stella and Robert’s love is the thing that really gets under Stella’s skin, and it foreshadows her predicament. She takes some two months to confront Robert, and is ultimately obliged to ask herself if she is the actor. Did she really ‘live in the shadow of an idea without grasping it’? Was she merely ‘keep[ing] up the appearance of love’? Is there ‘any such thing as an innocent secret’?

Such questions, such conflicts between the personal and the political, are matters of life and death indeed – and although there’s a sense of post-war rebirth in Bowen’s rather neat final chapter, the jigsaw appears neither complete nor consoling. In Jamesian, modernist ways, the uprights look ‘a little out of the straight’, the wall between the living and dead thin, the times uncertain.

Till next time in our uncertain times …

Elizabeth Bowen, The Heat of the Day (London: Jonathan Cape, 1948; repr. London: Vintage, 1998), p. 355. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 42, 46, 52, 107-8, 112, 203, 227, 233, 378.

On the question of authenticity, Bowen was active in the defence of London during the Blitz, and stayed in her Regent’s Park house until 1944, when bombs brought down her ceilings. See Victoria Glendinning, Elizabeth Bowen (New York: Avon, 1977), p. 167.