Cressida Lindsay’s Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces (1963)

The child’s-eye view

I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

Today I look at Cressida Lindsay’s superb Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces, and consider why it’s a lost novel.

I haven’t seen any theatre this week, partly because I’m halfway through the six seasons of Better Call Saul, which is so well-constructed it’s hard not to agree with Stephen Greenblatt in this New Yorker article that ‘deep absorption’ in long-form television is ‘comparable to literary study’.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend; if you’re in the UK, enjoy the sun and the bank holiday.

Thanks for subscribing.

Sam

I don’t know if this is still the case, but in the twentieth century, many Australian children would have encountered the work of Norman Lindsay – that writer, critic and artist who inspired the 1994 Hugh Grant film Sirens. Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding (1918) is an iconic work of children’s literature in Australia, an irresistible fantasy, gloriously illustrated, about a curmudgeonly steak-and-kidney pudding named Albert who can regenerate after he is eaten (from memory, I think he can also change from savoury to sweet and become a Christmas pudding).

Two of Lindsay’s sons, Jack and Philip, were UK-based novelists and historians. I’ve not read any of their work, except, as part of my research for Gabriel, Jack’s The Monster City, an enjoyable book about Daniel Defoe’s London, though the kind that covers Aphra Behn in a single paragraph.1

Until this week, I’d never encountered the work of Philip’s daughter Cressida Lindsay (1930-2010). On the evidence of her second novel, Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces, it’s my loss.2 She wrote four novels, all published in the 1960s and all now out of print – a fifth, unfinished, was published as an ebook in 2016. For many years she lived in a Norfolk commune for artists, and after her success as a novelist, she struggled with alcoholism, worked tirelessly for AA, and cared for her husband when he developed dementia.3 Two short 1970 films about her life in the commune, in which her sincerity shines through, can be viewed here and here.

Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces is set during the Second World War, mostly in London’s Fulham. It tells the story of Rachel, a half-Jewish ten-year-old who has been told nothing about her heritage, and so understands it only in terms of the snippets of information she gleans about Hitler, and the antisemitism she endures from Stan, a local bully.

We know from the title where Rachel’s father is; her charismatic mother Lucy, meanwhile, is in ‘pieces’ because she’s an alcoholic, incapable of caring for herself, let alone her daughter. Thus – in a reversal common to novels with child characters – the adult is immature and the child must become a grown-up, and, as the Luftwaffe’s bombs fall, we follow Rachel as she looks after Lucy, plays on bomb sites, becomes friends with a rag-and-bone man, and negotiates streets ruled by Stan.

This, then, is one of those clever books for adults in which a world is brought to life through the eyes of a child – though the narrator is not a child. Most of the adults responsible for Rachel have forgotten what it means to be young, while Rachel is always vaguely aware of the compromises and corruptions of the old. One atypically sympathetic adult looks at her and

wondered how much Rachel knew about her mother and came to the conclusion that the child was innocent in as much as she had withdrawn from the reality of the situation and saw only its outline. (p. 172)4

Seeing only the ‘outline’ of things is precisely how the narrative voice operates here: it is omniscient, yet, because the story is Rachel’s, paradoxically limited, childishly naïve. This is a literary technique with a long history, and Lindsay’s child characters, and her London, recall the child characters and London of the writer who perfected it, Charles Dickens. In Dombey and Son, Little Paul is dying but doesn’t realise it, and when the narrator tells us,

there seemed to be something the matter with the floor, for he couldn’t stand upon it steadily; and with the walls too, for they were inclined to turn round and round, and could only be stopped by being looked at very hard indeed,

we experience the poignancy and pain of a child’s-eye view that never quite sees everything: we are asked to fill the text’s gaps.5 The distance between Rachel’s ingenuousness and our adult insight likewise gives Lindsay’s novel much of its power. Often, Rachel’s naïveté is charming; often, it leads her into danger; always, we understand that the child does not understand just how much she is being neglected.

Two quick things I loved:

Firstly, Lindsay makes the compelling point that particularly for children, war can be as liberating as it is confining, as thrilling as it is terrible. Tragedy is contiguous with joy; humans can be ‘pleased and excited’ (p. 122) by violence and death.

Secondly, the novel is excellent on how, during times of privation, hopelessly non-functional belongings become deeply meaningful to us. Lucy’s handbag contains her whole life. The rag-and-bone man – who teaches Rachel that Stan’s ‘on Hitler’s side’, and that ‘[e]verybody’s half something but we all have the same blood’ (p. 91) – lives in a Dickensian curiosity shop among ‘teapots without lids, lids without teapots’. (p. 87) When Rachel is evacuated from London, she opens her bag on the train to find that Lucy – belatedly and extravagantly thoughtful as only an alcoholic can be – has packed Rachel’s

ration book and sweet coupons, a pocket book, a diary of two years back, a book she had read twice but whose familiarity was good to hold, a photo of herself and Lucy taken in the back garden standing close together and unrecognizably happy, one of her school exercise books and an artificial flower she had given Lucy the Christmas before. She spread everything out over the seat and then slowly packed them again, leaving out the book. Then she placed the suitcase by her side and sat down.

She opened the book and burst into tears. (p. 153)

Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces is difficult to get hold of now, and while I was reading such beautiful and cleverly constructed passages, I kept wondering why it has disappeared.

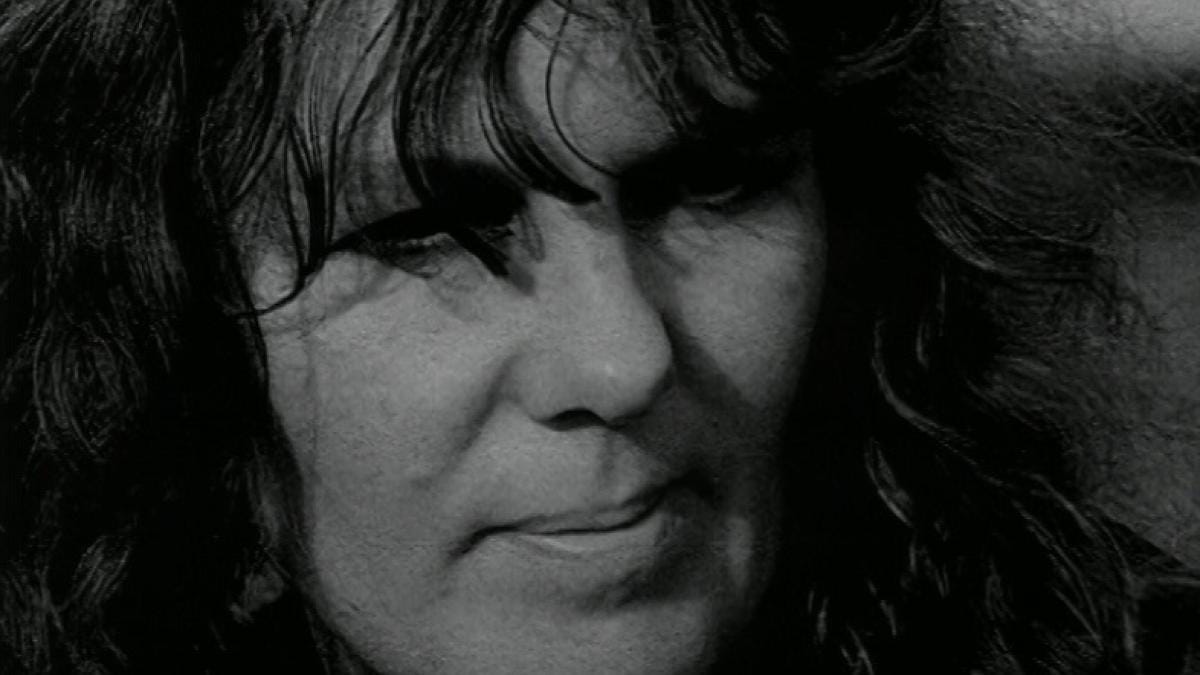

Putting aside the most obvious and dispiriting reason – that many first-rate books by women disappear simply because they’re by women – surely the fact that Lindsay had nothing published after her fertile period in the 1960s impacted negatively upon her long-term reputation. It’s also possible her title hasn’t helped: it’s too literal, and at the same time elusive. Then there’s the marketing by her early publishers, which looks atrocious. The back-cover blurb of the 1965 Panther reissue (pictured above) declares it a ‘shocking’ book in which ‘Mum sinks into drunken promiscuity [as] Rachel takes to the high life roaming the streets shop-lifting and looting’. This view of a story about a girl who does her best to survive the 1940s seems to me a very 1960s misreading: it makes Rachel sound as if she’s just stepped out of a swinging 60s film about delinquent youth.

Finally, there’s the novel’s ending.

We grow to love Rachel for her independence, instincts, discernment concerning friends and enemies, capacity for forgiveness, and sense of justice. At one point, she sees the film Bambi, a potentially insufferable reference which works, because Bambi is shot but survives – which is precisely what we want for Rachel. Her childhood reminded me here and there of Jane Eyre’s – what we want is for her story to become a Bildungsroman, with a Cinderella ending, as for Jane.

This nearly happens, but then there’s a turn of events – I won’t reveal what it is – that is distressing, and, in publishing terms, utterly uncommercial. This is a well-observed and always sad tale about a child who is let down again and again, and Lindsay has no time for the consolation to be found in a children’s story, a story like her grandfather’s, in which the owners of the magic pudding overcome both Pudding Thieves and society’s corrupt institutions to live happily ever after.

The ending to Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces is so troubling and disheartening that it’s hard to avoid the feeling that like one of her characters, Lindsay believes to the marrow of her bone that ‘it’s a sorry world’ (p. 100). There is hope in the book, but its climactic hopelessness is, I think, the main reason it has been consigned to oblivion.

This isn’t just. I admire Lindsay for her ending. Although it’s extremely difficult for the reader, what happens can happen. This is a truthful novel about childhood, and an important work to childhood studies. It should be back in print.

Jack Lindsay, The Monster City: Defoe’s London 1688-1730 (St Albans: Granada, 1978), p. 109.

Lindsay’s Wikipedia page suggests that Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces was her first novel, but in fact No Wonderland was first published in 1962. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cressida_Lindsay [accessed 27 May 2022].

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/nov/25/cressida-lindsay-obituary [accessed 27 May 2022].

Cressida Lindsay, Father’s Gone to War and Mother’s Gone to Pieces (London: Anthony Blond, 1963; repr. London: Panther, 1965), p. 172. Other page numbers in this newsletter refer to this edition.

Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (1848; repr. London: Mandarin, 1991), p. 204.

Fascinating study, as always, and another writer I haven't come across. I love the title of the book. Thank you for continuing to bring these often neglected women writers to our attention!