I’m a playwright who writes about twentieth-century novels and other literary/theatrical matters. Subscribe to The Essence of the Thing with your email address to have my newsletter delivered to your inbox. It’s free.

Hello,

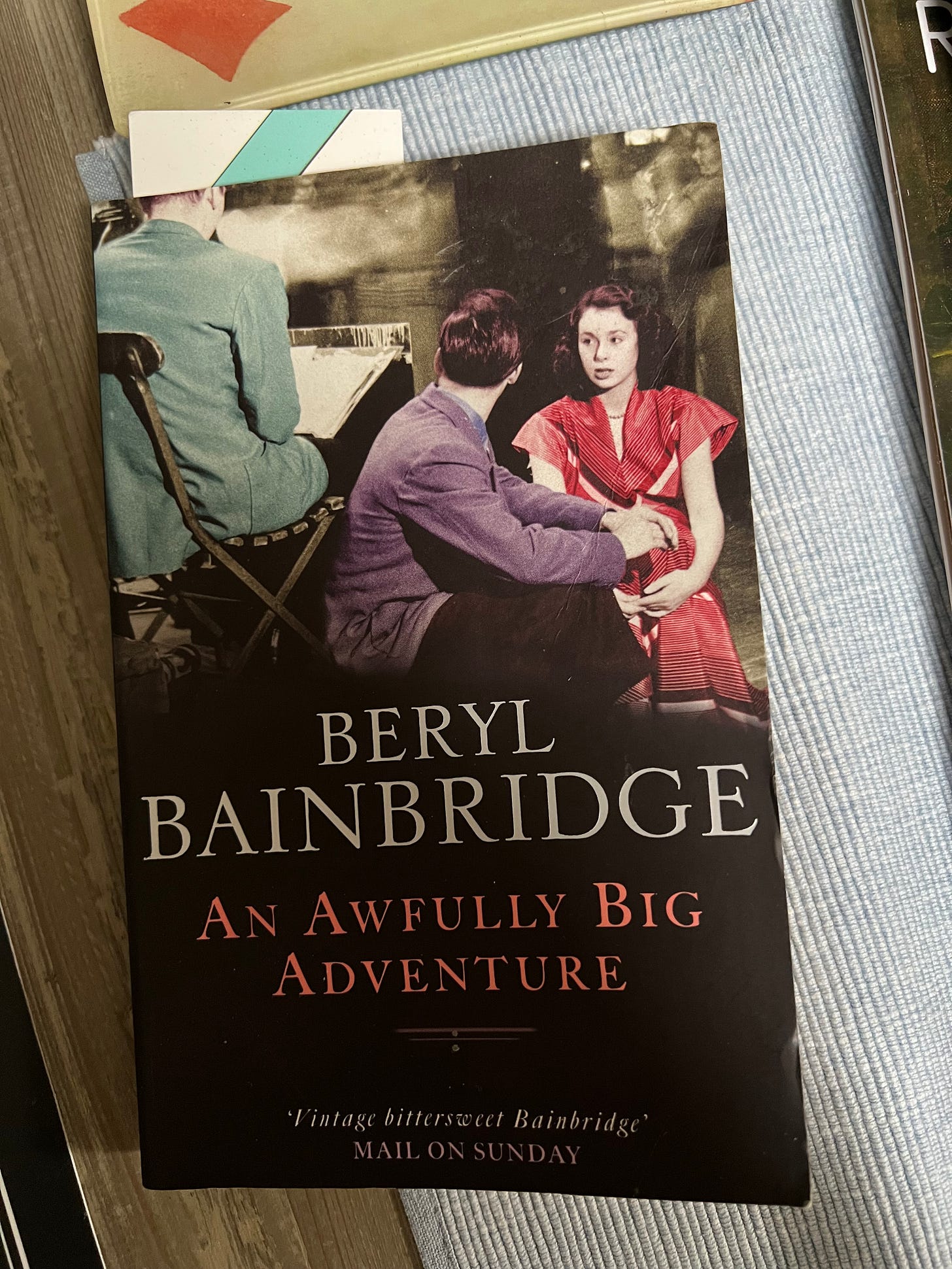

This week, some reflections on Beryl Bainbridge’s An Awfully Big Adventure and its intersection with Peter Pan.

This is my second-to-last last newsletter before a summer break. Thanks to the Kevin Elyot Award, I’m going to be spending some of that break in the Kevin Elyot archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection.

If you don’t know Elyot’s plays, they are exquisitely constructed chamber works about middle-class gay life in England from the 1960s to the early 2000s: his most famous, My Night with Reg (1994), won the Olivier Award for Best Comedy in 1995, though it’s far from just a comedy.

Looking through Elyot’s notebooks for his 1998 play The Day I Stood Still (which I rate above Reg) has been very moving: one fascinating thing (and consoling, for a playwright) is Elyot’s tendency to write notes of doubt, self-criticism, and self-motivation.

‘DON’T TURN another play into an Everest’, he scribbles on the first page of his first notebook; on page 31, there is an affectingly commonplace ‘Make characters REAL, BELIEVABLE’; and on page 32, a certain godlike playwright bears down on him intimidatingly: ‘[Pinter wrote play in 4 weeks!]’ (the square brackets are Elyot’s).1

After I return in September, the orbit of The Essence of the Thing will expand a bit to include pieces on Elyot’s six original plays and his writing process, on some of his adaptations, and on his never-produced BBC adaptation of Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library.

I hope some of you will be interested in these. There will be plenty of newsletters about lesser-known twentieth-century novels as well: authors moving to the top of my living-room pile include Molly Keane, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Dymphna Cusack, C.L.R. James and Peter Carey.

Thank you so much for reading. I appreciate every subscription, and if you know of people who may be interested in my thoughts on the Kevin Elyot archive (and other things), please tell them that they can subscribe for free with their email address.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend,

Sam

What are the notable twentieth-century novels for adults about the theatre? (Perhaps it’s silly to say ‘for adults’ – I didn’t come to Noel Streatfeild’s Ballet Shoes till I was in my 30s and loved it. And I keep meaning to read Pamela Brown’s The Swish of the Curtain – I know, I know, a deprived childhood.)

Two of my favourites are Michael Blakemore’s Next Season and Penelope Fitzgerald’s At Freddie’s, about which I’ll write newsletters one day; I touch upon Fitzgerald’s gorgeous and deceptive novel below. There’s Mikhail Bulgakov’s Black Snow and Angela Carter’s Wise Children. There’s Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea – though that’s not really about the theatre but about the life of a theatre director. The Good Companions and Lost Empires by J.B. Priestley are in my colossal to-be-read pile, glowering at me theatrically as I type this, as is W. Somerset Maugham’s Theatre.

And there’s An Awfully Big Adventure.

Beryl Bainbridge’s short, satirical, intriguingly gloomy novel is set in a 1950s Liverpool still recovering from the war, and concerns the melodramas of the members of a repertory theatre company in this straitened decade: their loves, secrets, lies, jealousies, betrayals. We enter their seedy backstage world with the 16-year-old Stella, who joins the company as an assistant stage manager. In essence, the story is about her loss of innocence, her coming of age.

It takes its title, of course, from another story about lost – and arrested – innocence, J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. According to Peter, on the verge of drowning in the Mermaids’ Lagoon, ‘To die will be an awfully big adventure’; according to one of Barrie’s illuminating stage directions, Peter does not understand (at the play’s climax) the older Wendy’s desire for him because of

something to do with the riddle of his being. If he could get the hang of the thing his cry might become “To live would be an awfully big adventure!” but he can never quite get the hang of it, and so no-one is as gay as he.2

Needless to say that in a post-Freudian world, this is all compellingly weird, and An Awfully Big Adventure is very interested – like most appropriations of Barrie, or examinations of his life – in that weirdness, and the weirdness of the theatrical traditions surrounding it, not least the tradition that allows actresses well into their middle age to play the pubescent Peter. The year is 1950, and Mary Deare, ‘possibly the best Peter since Nina Boucicault’, has played the role since 1922.3 She is ‘built like a swallow’, which suits the flying, but gets serious ‘abrasions in her armpits’ from the harness because – suffering for her art, holding on to her youth like Peter – she refuses to wear a protective vest.

But the novel’s more complex Peter (and Wendy) figure is Stella. Abandoned by her actress manqué mother, brought up by her aunt and uncle in a boarding house, she’s a fascinating character: brusque, impetuous, disarmingly honest, with an imagination inflamed by the ‘melancholy and madness’ of the poetry she loves. She is the smartest person in the company, but – and this is very cleverly and subtly done – the most naïve. Much about life is just beyond her field of vision.

We follow the backstage shenanigans surrounding productions of Priestley’s Dangerous Corner and Bernard Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra – in which Stella plays the boy king Ptolemy, just as Bainbridge once did at the Liverpool Playhouse – until we get to Peter Pan.4 At the read-through, the director Meredith Potter says to the actors:

There are numerous books on the meaning behind this particular play […] I’ve read most of them and am of the opinion they do the author a disservice. I’m not qualified to judge whether the grief his mother felt on the death of his elder brother had an adverse effect on Mr Barrie’s emotional development, nor do I care one way or the other. We all have our crosses to bear. Sufficient to say that I regard the play as pure make-believe. I don’t want any truck with symbolic interpretations.

What we come to realise is that this affected anti-intellectualism is Bainbridge’s red herring: Peter Pan eerily permeates every page of An Awfully Big Adventure; it is a long way from ‘pure make-believe’ by very virtue of the fact that it is being produced; and symbolic and psychoanalytic interpretations of its intersections with the parentless Stella are unavoidable. This is a story about a Lost Girl.

A little like Peter and/or Wendy, she is in love with someone who can’t return the love (Meredith), and the reason (his homosexuality) sits outside of her understanding. The Never Land she enters – theatre – is as menacing and as morally ambiguous as Barrie’s. As for Peter, her new life exists in uneasy tension with a world never quite left behind. As for Peter, Never Land is a place that – for reasons she does not comprehend but which we come to – she can never leave. The production doubles the roles of Captain Hook and Mr Darling as per tradition, and there are echoes of these characters in the life and death of the actor who plays them, with whom Stella has a relationship.

Fundamentally, like Peter, Stella is motherless, and the mother’s story – the mystery, really – is unravelled in the most devastatingly simple and poignant way.

Here and there, An Awfully Big Adventure reminded me of Fitzgerald’s At Freddie’s (1982), which is set in a 1960s London stage school for children, and also references Peter Pan. Fitzgerald’s book can be read in two ways – as an affectionate and witty nod to a kind of English theatre that has vanished; or as examination of child abuse in the theatre, an indictment of a Dickensian forcing-house ruled by a Fagin-like tyrant who is ultimately responsible for the death of a child under her care. It is possible to enjoy the book according to the first reading by completely denying the second – as if watching the tune-filled musical Oliver! and denying the horrors of Oliver Twist.

Like At Freddie’s, Bainbridge’s book looks back to a kind of English theatre that has disappeared, has lashings of wit, and relishes the sublimely solipsistic behaviour of actors and directors. But there can be no double reading here: Bainbridge’s theatre is obviously lonely, melancholy and cruel. I think the setting is a coat-hanger upon which she drapes a story about the sadness of life; and Stella is such a tough Liverpudlian that it seems certain she will survive the sadnesses into her adulthood. But where other theatre novels glamorise theatre’s big heartedness and sense of community – the thrill of the swish of the curtain, the smell of the greasepaint, the roar of the crowd – Bainbridge finds something more, something much harder: selfishness, clinically depressed artists, stupidity, dishonesty, and terrible sexual violence.

The 1950s setting does not, sadly, diminish the relevance of all this in 2023; and as someone who works in the theatre, I found it a thoroughly convincing account of theatre’s capacity for ghastliness.

As the narrator says of Mary Deare’s Peter Pan, the adventure is ‘downright sinister’.

Kevin Elyot Archive, University of Bristol Theatre Collection: KE/3/32/1, yellow notebook 1 (of 3).

J.M. Barrie, Peter Pan (1904; repr. London: Samuel French, [n.d.]), pp. 48, 83.

Beryl Bainbridge, An Awfully Big Adventure (London: Duckworth, 1989; repr. London: Abacus, 2003), p. 137. Subsequent quotations are from pp. 11, 96-97, 124, 159.

<https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2005/oct/04/theatre.berylbainbridge> [accessed 23 July 2023].

We’ve not discussed Restoration or Tremain. The Road Home has a big scene at a major opening night at the Royal Court. On a Sunday. Lousy editing, yes, but..

Typically illuminating. Thank you. Shamefully, I have only seen the (very good) film of An Awfully Big Adventure which I recommend highly, not least for Hugh Grant serving notice on what a good actor he is. (Something most critics have only recently caught up with.) Not read (yet) At Freddie’s either by the excellent Fitzgerald.

I am largely allergic to mist backstage adult novels because they tend to get so much badly wrong - the theatre passages in Rose Tremain’s The Road Home are particularly egregious - but have you read Anthony Quinn’s Curtain Call. Set in theatreland in 1930. All the detail is spot on. Terrific book which has been made into a film to be released soon, script by Patrick Marber starring Ian McKellen in the title role of The Critic.